A blog dedicted to the history of arcade video games from the bronze and golden ages (1971-1984).

Sunday, October 28, 2012

Wednesday, October 24, 2012

A Trip to the Penny Arcade - Circa 1907

Today's post

is a bit a departure. One of my favorite "video game" books is Dick

Bueschel's Arcade 1.

In truth, it really isn't a video game book, though it does cover seven video games in its 300+ pages. It is the

first of a planned five-volume series on the history of "arcade"

machines (basically, any coin-operated amusement machines other than jukeboxes,

pinball, slot machines, trade stimulators, or vending machines ). The volume

was subtitled "Ancient Lands to Wonderlands: 3600 BP to 1905". To

give you an idea of the depth of information in Bueschel's books, look at his

Pinball 1, the first of a planned 10-volume series on pinball. While most

histories of pinball start with Gottlieb's Baffle

Ball, Pinball 1 has a 100-page history section that ENDS with Baffle Ball.

Arcade 1 has

a 150-page history of arcade games, a price list, a game list, a section

covering 100 games from all eras, and a bonus section. While it starts at 3600

BP, it really concentrates on the period from the 1880s to 1905. Sadly, Dick

Buesehel passed away before completing any more volumes in either series.

Anyway, on to

the subject of today's post. The "bonus section" in Arcade 1 consists

of a guide published around 1907 by the Mills Novelty Company of Chicago called

"Mills Penny Arcades". It is a guide to operating a penny arcade (the

heyday of the penny arcade was the 1902-1907 period).

Mills Novelty

Company was one of the two leading producers of arcade machines of the era (the

other was Caille Brothers of Detroit). They are probably best known for their

slot machines (particularly the Owl introduced in 1897 and the Liberty Bell

introduced in 1906).

The guide

contains a list of suggested machines for various arcade setups. The most

expensive setup (costing around $5,000) includes the following. I think this

gives a nice picture of what a penny arcade would have been like circa

1907. Notes about the various machine

types follow:

·

24

Auto-Stereoscopes and 37 sets of 15 views each· 8 Illustrated Song Machines with 1 set of 12 views and 1 record each, plus 8 extra sets of 12 views

· 5 Quartoscopes and 10 sets of 4 dozen views

· 5 Automatic Phonographs with 1 record each plus 5 extra records

· 3 Illusion Machines

· 1 new Owl Lifting Machine

· 1 new Owl Dumbbell Lifting Machine

· 1 new Owl Flashlight Lifting Machine

· 1 new Owl Chimes Lifting Machine

· 1 Flashlight Grip Machine

· 1 Submarine Lung Tester

· 1 Rubber Neck Lung Tester

· 1 Hat Blower

· 1 Searchlight Grip and Lung Tester

· 1 Bag Punching Machine

· 1 Pneumatic Punching Machine

· 1 new Vertical Punching Machine

· 1 Sibille Fortune Teller plus 2,000 extra cards

· 1 large Horoscope Fortune Teller plus 2,000 extra cards

· 1 Conjurer Fortune Teller

· 1 pair Jumbo Success Fortune Teller (one for ladies, 1 for gentlemen)

· 1 Madame Neville Palmist with 1,000 letters plus 1,000 extra letters

· 1 Cupid Post Office with 1,000 letters plus 1,000 extra letters

· 1 Mills Perfect Weighing Machine

· 1 Large Electric Shock Machine

· 1 Doctor Vibrator

· 1 Lady Perfume Sprayer

· 1 24-Way Multiple Postal Card Machine with 2,000 cards plus 2,000 extra cards

· 1 Emblem Embossing Machine with 600 emblems plus 500 extra emblems

· 1 Windmill Candy Machine

· 1 Combination Money Counter for pennies

· 1 Automatic Pianola with 1 roll of music plus 2 extra rolls (4 pieces to the roll)

· 1 Cashier's Desk

· 1 Repair Outfit

· 1 Key Board with lock

· 48 Key Rings

· 96 Key Tags

· 36 Coin Bags

· 100 Perforated brass 1c brass slugs

· 50 Weekly Statement Sheets

· Various signs

Stereoscopes, Quartoscopes, Illusion

These were

peep shows that contained a number of stereo views or photos. The Quartoscopes

contained 4 sets of 12 views each. Interestingly, the list does not contain any

movie viewers. Edison's Kinetoscope appeared around 1894 and the Mutoscope

followed about a year later. Kinetoscope and Mutoscope parlors were hugely

popular in the 1890s but soon disappeared (the Kinetoscope had a loop of film,

the Mutoscope had a bunch of still images that were flipped to give the

illusion of motion). They were eventually supplanted by the rise of the

Nickolodeon and other movie houses.

|

| Quartoscope |

Automatic Phonograph, Illustrated Song

Machines

Automated

phonograph parlors were also common in the 1890s. Edison didn't actually

envision the phonograph as being primarily an amusement device (he thought it

would be put to more serious uses). Phonographs in phonograph parlors included

either 3 or 4 individual listening tubes or one large one that could accommodate

about four people. The automatic phonograph also faded from view around this

time and was replaced by coin-operated pianos, orchestrions (which included

percussion instruments etc.) and other music machines. It wasn't until the

first amplified model in 1927 and the repeal of prohibition that automatic

phonographs came back (they were eventually called jukeboxes).

The Illustrated Song Machine was a combination peep show and automatic phonograph.

The Illustrated Song Machine was a combination peep show and automatic phonograph.

Lifting Machines, Punching Machines and Grip Testers

Athletic test

machines like this were really the first arcade games. The first coin-op devices

overall were vending machines (Heron/Hero of Alexandria described a coin-op holy

water dispenser in 215 BC but that was kind of a fluke). The first coin-op

amusement machines were "exhibition machines" like Henry Davidson's Chimney Sweep of 1871 or William T.

Smith's The Locomotive of 1885

(considered the first U.S. made coin-op amusement machine). In the 1880s,

various strength testers etc. began to appear in bars and taverns (actually,

they had been there before but in the 1880s people started adding coin slots).

Lifting machines involved pulling on handles. grip testers involved squeezing handles

etc.

|

| Chimes Lifter |

Lung Testers

Another form

of athletic tester, these involve blowing into a tube for as long as

possible. The Mills Submarine and Rubberneck

models were pretty cool. The first had a case with four tiny deep sea

divers on strings. As you blew, they were raised one-by-one. The second had a

mannequin with a neck that you stretched. The Hat

Blower wasn't bad either.

Shockers (and Doctor Vibrator)

These

were some of the most bizarre machines of all. Believe it or not, people would actually pay money for the privilege of

receiving an electric shock. After depositing their coin, they would grab a

pair of metal handles and wait while the current passed through their bodies.

They were usually billed as therapeutic (hence "Doctor" Vibrator -

and shame on you for what you were thinking). Two of the most popular with

Midland Manufacturing's Electricity Is

Life and Exhibit Supply's Electric

Energizer (aka Spear the Dragon), in

which you tried to hold the handles the until a dragon-slaying knight crossed a

bridge to spear a dragon, an act rewarded by the ringing of a bell.

Fortune Tellers, Cupid Post Office,

Card Venders

Coin-op

fortune tellers have been around since at least 1867. One of my favorites was

the Roovers Brothers Educated Donkey (with

a donkey dispensing fortunes). Cupid's

Post Office delivered love letters. Other card venders delivered

horoscopes, postcards etc. In the post-World-War-I years, card venders became

the backbone of the coin-op industry and Exhibit Supply Company was the leading

manufacturer by far.

The perfume

sprayer was just what it sounded like (one model, called Take the Bull By the Horns had you grab the horns of a steel bull's

head then get spritzed with perfume). The Windmill was a candy machine with a

three-bladed "windmill" that spun around. The embossing machine

printed out metal tags.

Monday, October 22, 2012

Update On Reiner Foerst's Nurburgring

I just dicovered some excellent new information on Nurburgring here:

http://historyofracinggames.wordpress.com/installment-three/

The website is Lance Carter's History of Racing Games and had a LOT more info about the game (including quotes fro Dr. Foerst himself).

The first thing I noticed is that I spelled Reiner's name wrong - it is actually Foerst, not Forest.

You can read the articles yourself, but among the many fascinating details

http://historyofracinggames.wordpress.com/installment-three/

The website is Lance Carter's History of Racing Games and had a LOT more info about the game (including quotes fro Dr. Foerst himself).

The first thing I noticed is that I spelled Reiner's name wrong - it is actually Foerst, not Forest.

You can read the articles yourself, but among the many fascinating details

- The first Nurburgring game was started in 1973, maybe even earlier (it isn't entirely clear from the website, but the idea may have come in 1971, before Pong)

- Midway co-founder Iggy Wolverton visited Foerst and led him to believe that a licencing deal was in the works (or at least Foerst somehow got that impression)

- Foerst produced a version of the game in a tilting sit-in cabinet, another in a rotating cabinet, and even a "competition" version that allowed 8 machines to be linked together (and this was in 1983/84).

- Interesting info about the game's sounds.

- Foerst claims that after he and Ted Michon met in the Dusseldorf bowling alley (where they bowled together), Michon called his "boss" and then became nervous, told Foerst he had no choice but to end the conversation, and left (though he does say that he and Michon continued to correspond afterwards, which matches what Michon told me).

Friday, October 19, 2012

Atari Head-To-Head Rifle Game and Other Patent Goodies

Researching a book on video game history often invovles poring over patent records. Sometimes they can be boring but more often than not I find somthing interesting. Here are a few I found recently.

First up is this patent filed on January 30, 1978 by John Romano and Roger Hector of Atari, Inc.

It is for a two-player, head-to-head ifle game (non video).

I've never seen this game on any list of Atari prototypes (at least not that I remember).

The screen in between the players had obstacles like trees and islands that blocked your opponent's shot. It also displayed the score. The object was to hit your opponent's target.

Here's another Atari patent. This one was filed on April 28, 1977 by Steve Bristow and David Dean.

Off the top of my head, I don't recall seeing this one either. It doesn't look anything like Qwak or Triple Hunt.

Of course, just because they patented something doesn't mean it got to play testing. I don't know if it even means they built a prototype.

This one's not quite as interesting. It's another Atari patent (actually, there were 2 patents). This one filed on September 23, 1977 by Peter Takaichi and Andrew Graybeal.

This one is for a booth-style video game cabinet. I know that Elcon Industries made a cabinet like this.

Finally, here's one from Williams. Filed July 5, 1983 by Leo Ludzia and Romeo Ishaya.

Ring any bells out there?

BTW, Ludzia also got patents for the duramold cabinet (with Gary Berge) and the Joust cocktail cabinet (with Eugenia Akopian).

And while we're on the topic of cabinet desginers (who rarely get any credit), here are a few more I've found:

Brad Chaboya - Atari - Gravitar

Regan Cheng - Atari - Puppy Pong, Hi-Way, Stunt Cycle

David Cook - Atari - Tank 8

Michael Cooper-Hart - Exidy - Robot Bowl, Star Fire

Terry Doerzaph - Gottlieb - Q*Bert

George Gomez - Midway - Tron, Discs of Tron, Spy Hunter?

Chaz Grossman - Atari - Puppy Pong

Mike Jang - Atari - Starship 1

Phillip Kearney - Atari - Wolfpack (prototype)

Verl Olsen - Gremlin - CoMotion

Lonnie Pogue - Gremlin - Hustle

Robert Runte - Fascination, Ltd - Fascination

A. Ryan - Bally/Midway - Tron

Kenneth Sauter - Atari - Indy 800, Quiz Show

And some cabinet artists

Ray Maninang - Exidy - Crossbow, Cheyenne

Constantno Mitchell - Williams - Robotron

George Opperman - Atari - lots

Pat "Sleepy" Peak - Exidy - Alley Rally, Death Race, Score, Spiders From Space (prototype)

Kazunori Sawano - Namco - Galaxian

R. Scafaldi - Midway - Tron

Richard Taylor - Midway - Tron

First up is this patent filed on January 30, 1978 by John Romano and Roger Hector of Atari, Inc.

It is for a two-player, head-to-head ifle game (non video).

I've never seen this game on any list of Atari prototypes (at least not that I remember).

The screen in between the players had obstacles like trees and islands that blocked your opponent's shot. It also displayed the score. The object was to hit your opponent's target.

Here's another Atari patent. This one was filed on April 28, 1977 by Steve Bristow and David Dean.

Off the top of my head, I don't recall seeing this one either. It doesn't look anything like Qwak or Triple Hunt.

Of course, just because they patented something doesn't mean it got to play testing. I don't know if it even means they built a prototype.

This one's not quite as interesting. It's another Atari patent (actually, there were 2 patents). This one filed on September 23, 1977 by Peter Takaichi and Andrew Graybeal.

This one is for a booth-style video game cabinet. I know that Elcon Industries made a cabinet like this.

Finally, here's one from Williams. Filed July 5, 1983 by Leo Ludzia and Romeo Ishaya.

Ring any bells out there?

BTW, Ludzia also got patents for the duramold cabinet (with Gary Berge) and the Joust cocktail cabinet (with Eugenia Akopian).

And while we're on the topic of cabinet desginers (who rarely get any credit), here are a few more I've found:

Brad Chaboya - Atari - Gravitar

Regan Cheng - Atari - Puppy Pong, Hi-Way, Stunt Cycle

David Cook - Atari - Tank 8

Michael Cooper-Hart - Exidy - Robot Bowl, Star Fire

Terry Doerzaph - Gottlieb - Q*Bert

George Gomez - Midway - Tron, Discs of Tron, Spy Hunter?

Chaz Grossman - Atari - Puppy Pong

Mike Jang - Atari - Starship 1

Phillip Kearney - Atari - Wolfpack (prototype)

Verl Olsen - Gremlin - CoMotion

Lonnie Pogue - Gremlin - Hustle

Robert Runte - Fascination, Ltd - Fascination

A. Ryan - Bally/Midway - Tron

Kenneth Sauter - Atari - Indy 800, Quiz Show

And some cabinet artists

Ray Maninang - Exidy - Crossbow, Cheyenne

Constantno Mitchell - Williams - Robotron

George Opperman - Atari - lots

Pat "Sleepy" Peak - Exidy - Alley Rally, Death Race, Score, Spiders From Space (prototype)

Kazunori Sawano - Namco - Galaxian

R. Scafaldi - Midway - Tron

Richard Taylor - Midway - Tron

Wednesday, October 17, 2012

Video Game/Pinball Combinations

Following up on my last post, video games and pinball

machines have long been kissing cousins and over the years a number of

not-very-successful attempts have been made to combine the two.

Exidy also released the cocktail-table game Table Pinball, presumably a cocktail version of TV Pinball.

This game looks virtually identical to TV Pinball except for minor variations in the cabinet and possibly different color overlays. Some sources list the game as coming out in 1973. If it is the same game, it seems a bit odd that Chicago Coin's version came out first as it seems more likely to me that they would have licensed it from Exidy rather than vice versa. For instance, they did license Exidy's Destruction Derby, which they released as Demolition Derby.

Video Pinball (Atari, 1979)

Now HERE was a decent attempt at a video version of pinball. Designed by Ed Logg, Dave Stubben, and Dan Pliskin, it used mirrored-in graphics to provide images of an actual pinball playfield (which was designed over a foam core painted with fluorescent paint). It had flippers, drop targets, rollovers, and thumper bumpers. It even let you nudge the game by pushing on the control panel. Atari made 1,505 of them and the Replay operator's poll ranked it as the 10th best-earning video game of 1979. .

Here's a quick look at some of them (remember, this blog is pre-1985 coin-op only, so no Pinball 2000 here).

1)

PINBALL

VIDEO GAMES

The most common way to combine the two was to create a

video version of pinball, an idea that was tried from the earliest years of

coin-op video games.

Clean

Sweep (Ramtek, 1973)

OK, this wasn't exactly a video pinball game but it was

fairly close. It was a ball-and-paddle variant in which the player tried to

knock down a field of dots with the ball (since I haven't actually played it, I

don't know if your ball bounced off the dots or not, though from the name it

kind of sounds like they didn't). Designed by Howell Ivy (who later went to

Exidy), it was a predecessor of sorts to Atari's Breakout

TV

Pinball (Exidy, 1975)

It wasn't Exidy's first game, as some sources have it.

That honor goes to Thumper Bumper

(which, despite the name, was a straight Pong

clone, though it used a color overlay). TV Pinball appears to be a souped-up version of Clean Sweep and unlike the Ramtek game,

this one DID promote itself as a video version of pinball, referring to the

dots as "bumpers". It also had pockets at the side of the screen and

a moving target at the top. Ivy came to Exidy in 1975, probably too late to

design TV Pinball. I suspect that

the game was designed by John Meltzer, who also came from Ramtek (assuming it

wasn't designed by Chicago Coin - see below).Exidy also released the cocktail-table game Table Pinball, presumably a cocktail version of TV Pinball.

TV Pin

Game (Chicago Coin, 1974?)

This game looks virtually identical to TV Pinball except for minor variations in the cabinet and possibly different color overlays. Some sources list the game as coming out in 1973. If it is the same game, it seems a bit odd that Chicago Coin's version came out first as it seems more likely to me that they would have licensed it from Exidy rather than vice versa. For instance, they did license Exidy's Destruction Derby, which they released as Demolition Derby.

TV Flipper

(Midway,

1975)

Another game very similar to the above two. The flyer billed

it as "A video game with all the excitement of pinball" (somehow, I

doubt it).

Flipper

Ball (Cinematronics, 1976?)

OK, what's the deal with this game. This one is identical

to TV Pin Game (even the screenshot

on the flyer is exactly the same), except that it came in a cocktail cabinet.

Some sources indicate that this game wasn't actually released until 1977 (I

think I actually found a release notice in Vending

Times or Replay but I'd have to

check). Why they would be releasing a

copy of a 2-3 year old game beats me. By the time they released it, Chicago

Coin was on the verge of bankruptcy if not actually bankrupt (their assets were purchased by the newly formed Stern Electornics).

|

| Screnshots from the flyers of Chi Coin's TV Pin Game and Cinematronics' Flipper Ball. Or is it Flipper Ball and TV Pin Game? |

Video Pinball (Atari, 1979)

Now HERE was a decent attempt at a video version of pinball. Designed by Ed Logg, Dave Stubben, and Dan Pliskin, it used mirrored-in graphics to provide images of an actual pinball playfield (which was designed over a foam core painted with fluorescent paint). It had flippers, drop targets, rollovers, and thumper bumpers. It even let you nudge the game by pushing on the control panel. Atari made 1,505 of them and the Replay operator's poll ranked it as the 10th best-earning video game of 1979. .

Pin

Dual (Atari, 1980/Unreleased)

A two-player, head-to-head version of Video Pinball. It was scheduled for

field testing but I don't know how far along in development it got.

Solar

War/Superman/Orion XIV (Atari, 1979/Unreleased)

Video

Pinball actually had a sequel of sorts in the unreleased Solar War created by Mike Albaugh in an effort to find a use for

the remaining unsold Video Pinball

PC boards and see if there was still a market for similar games. Solar War’s original name had been Super Man and the game was to be a

video version of the pinball game of the same name released in March 1979. When

DC demanded additional royalty payments, however, Atari had to come up with

another name. Because the game featured a “spell out”, the new name had to

match the same 5 letter-3 letter pattern of the original, hence Solar War (another suggestion was Orion XIV). The game also featured a

unique control arrangement – the entire control panel could be moved up and

down to tilt the playfield. By the time the game was ready, Atari’s production

lines were running full-tilt producing Asteroids

games and only five units were built (though around 300 “conversion kit”

versions were reportedly sold to a Greek operator).

2)

Pinball

Video Games in a Pinball Cabinet

A mutant creation if there ever was one,. Mounting a

video game monitor in a pinball cabinet doesn't seem right.

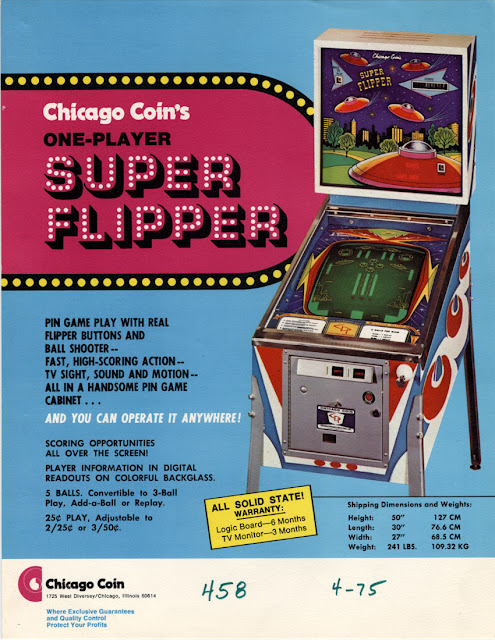

Super

Flipper (Chicago Coin, 1975)

Chicago Coin made just about every type of coin-op game under the sun but they were rarely the top producer in any genre. During the 60s they ranked well behind Gottlieb, Williams, and Bally in pinball (though they might have been a distant fourth). Looking at this thing from a distance, you wouldn't know that it wasn't a pinball machine. It had an honest -to-gosh pinball cabinet complete with backglass, flipper buttons, and plunger. When you got closer, however, you knew there was something amiss when you saw the playfield.

I hate to admit it, but this thing actually looks pretty darned interesting to me. The ball started off moving left and right across the playfield. Pulling the plunger caused it to shoot downwards into play (OK, that part doesn't sound so interesting). The flipper buttons consisted of a sliding mechanism with a hole in it , that separated a light and a photocell. The further you pressed the buttons, the more the flippers moved.

Chicago Coin made just about every type of coin-op game under the sun but they were rarely the top producer in any genre. During the 60s they ranked well behind Gottlieb, Williams, and Bally in pinball (though they might have been a distant fourth). Looking at this thing from a distance, you wouldn't know that it wasn't a pinball machine. It had an honest -to-gosh pinball cabinet complete with backglass, flipper buttons, and plunger. When you got closer, however, you knew there was something amiss when you saw the playfield.

I hate to admit it, but this thing actually looks pretty darned interesting to me. The ball started off moving left and right across the playfield. Pulling the plunger caused it to shoot downwards into play (OK, that part doesn't sound so interesting). The flipper buttons consisted of a sliding mechanism with a hole in it , that separated a light and a photocell. The further you pressed the buttons, the more the flippers moved.

Star

Shooter (Meadows Games, 1975/Unreleased)

This was the same basic idea as Super Flipper. Meadows took it to the 1975 MOA show where it flopped and they never released it. Designer David Main ha this to say about it:

This was the same basic idea as Super Flipper. Meadows took it to the 1975 MOA show where it flopped and they never released it. Designer David Main ha this to say about it:

[David Main] When we went to the MOA show,

the game was a total dud. We thought it was cool because we were in love with

the technology but it was a dud because the people who like pinball play it

because of the mechanical aesthetics of it. They like the sound of the ball,

and you can’t just pretend to have a ball – it has to be a real ball.

So

we went from having a video game version to a mechanical version. In fact I had

a patent for a way of sensing the position of the ball on the playfield by

having the ball roll over coils. I would send out energy pulses to these

different coils that were located in different places on the playfield. When a

ball rolled over it, depending on how close it was, the ball would absorb some

of the energy that was sent out through this coil. There was one capacitor that

switched from coil to coil so that when you hit it with a pulse it would cause

a circuit to ring and by counting how many rings there were before the level

fell below a threshold I could determine how much energy had been absorbed.

I actually saw a photo of this game (I think in Vending Times) but don't have a copy

handy (I'll have to see if I can find one).

3)

Video/Pinball

Combinations

These games combined an actual (usually poor) pinball

game with an actual (usually poorer) video game. The result was not pretty. At

certain points, the pinball action would stop, then you'd have to take your

eyes off the pinball table and look up at the video monitor mounted above it to

play a simplified video game.

Baby

Pac-Man (1982, Bally/Midway)

Designed by Dave Nutting

Associates and Bally (much to Namco's chagrin, since they hadn't authorized the

game), this is probably the most well-known

video/pinball combination. The

pinball portion was designed by Claude Fernandez with art by Margaret Hudson.

Bally sold 7,000 units and the game reached #5 on Replay's Player's Choice charts.

Granny

and the Gators (1983, Ballly/Midway)

Bally's second

attempt at the genre. The pinball portion was designed by Jim Patla with art by

Margaret Hudson and Pat McMahon. This game was not without its charms. Some

claim that the video game portion led to Toobin'

but I don't know if that's true or not.

Caveman (1982,

Gottlieb)

With only 1,800 produced this one wasn't much of a success. The

pinball portion was designed by John Buras with art by Terry Doerzaph, David

Moore, and Rich Tracy. The video portion was a simple maze game in which a

caveman is pursued by dinosaurs. It was designed by Joel Krieger with hardware

by Jim Weisz and art by Jeff Lee (it was actually Lee's first work at Gottlieb

and he designed the graphics on an Apple II computer).

New

York Defense/Defence (1981, E.G.S./Telemach 3)

This one was shown at the Forainexpo show at Le Bourget

in Paris in December, 1981. It was made by the Italian company E.G.S. and

Telemach 3 (a company about which I know next to nothing, other

than that they had a booth at the show). It made its debut earlier at the Emada

show in Rome. I have seen almost nothing on this game anywhere. The Internet Pinball Database lists it as New York and gives only the name, company, and year of release. The other databases (pinside, arcade museum, arcade history) seem to take their info from IPD. I'm not even sure it IS a video/pin

combo.

All of the information comes from the January, 1982 issue of Replay, from which the following photo was taken (please excuse the very poor quality - I scanned it in black and white several years ago because, at the time, I was only interested in the text. I threw the actual issue away since I didn't have the space for it).

All of the information comes from the January, 1982 issue of Replay, from which the following photo was taken (please excuse the very poor quality - I scanned it in black and white several years ago because, at the time, I was only interested in the text. I threw the actual issue away since I didn't have the space for it).

The

Cube/Paparazzi? (unreleased?, Gottlieb)

Designed by Harry Williams. See the previous post for

details.

Monday, October 15, 2012

Harry Williams - Video Game Designer???

I recently came across an interesting article about pinball legend Harry Williams (founder of Williams Electronics)

http://archive.ipdb.org/russjensen/harryw.htm

On September 14, 1982, a year before Williams died, Russ Jensen talked to him on the phone.

During the conversation, Williams said that he was currently designing video games for Stern and for an unnamed Japanese company.

That is interesting enough in its own right, but he also mentioned that he had designed a video game/pinball combination that he sold to Gottlieb.

The video game portion had a Rubik's Cube theme and he thought that Gottlieb was going to call the finished game The Cube or Paparazzi.

AFAIK none of Williams' video game creations were ever released. Gottlieb did release the video/pin combination Caveman but that doesn't sound anything like the game Williams' described.

The two things that really jump out at me are that he said the game "used mirrors" and that the pinball and video game portions were "fully integrated".

From the description, that sounds an awful lot like the Pinball 2000 concept that Williams developed in the late 90s (chronicled in the documentary Tilt).

For those who don't know, Harry Williams was one of the absolute legends of pinball.

He started in the coin-op industry in 1929 and over the years he designed pinball games for just about every major manufacturer. His two most famous innovations were probably the first tilt device and Contact (often credited as the first machine with electricity, sound, and a kicker - though there were actually other machines that used them first).

It's hard to pick just one story from his career, but how about the tilt device?

http://archive.ipdb.org/russjensen/harryw.htm

On September 14, 1982, a year before Williams died, Russ Jensen talked to him on the phone.

During the conversation, Williams said that he was currently designing video games for Stern and for an unnamed Japanese company.

That is interesting enough in its own right, but he also mentioned that he had designed a video game/pinball combination that he sold to Gottlieb.

The video game portion had a Rubik's Cube theme and he thought that Gottlieb was going to call the finished game The Cube or Paparazzi.

AFAIK none of Williams' video game creations were ever released. Gottlieb did release the video/pin combination Caveman but that doesn't sound anything like the game Williams' described.

The two things that really jump out at me are that he said the game "used mirrors" and that the pinball and video game portions were "fully integrated".

From the description, that sounds an awful lot like the Pinball 2000 concept that Williams developed in the late 90s (chronicled in the documentary Tilt).

For those who don't know, Harry Williams was one of the absolute legends of pinball.

He started in the coin-op industry in 1929 and over the years he designed pinball games for just about every major manufacturer. His two most famous innovations were probably the first tilt device and Contact (often credited as the first machine with electricity, sound, and a kicker - though there were actually other machines that used them first).

It's hard to pick just one story from his career, but how about the tilt device?

Harry's first game

was 1932's Advance, a 10-ball game

that featured a number of mechanical gates that could be opened and closed with

a well-place shot. The game also included a visible coin chute to discourage

the use of slugs. One day, Williams noticed a

player in a nearby drugstore hitting the bottom of an Advance machine to make the gates open without hitting them with

the ball. Furious, Williams pounded five sharp nails into the machine to

discourage such tactics. Knowing that he needed a more practical (and humane) solution

he created a device consisting of a steel ball mounted atop a pedestal. If the

machine was jarred too violently, the ball would fall off the pedestal and make

contact with a metal ring, closing a circuit and bringing the game to a

premature end. He called the device a "stool pigeon". After returning

the machine back to the drugstore, one of the players activated the device and

said "Oh look, I hit it and it tilted. [1]"

Williams quickly renamed his creation the tilt device.

Wednesday, October 10, 2012

The Story of Rock-Ola Video Games (Part 3)

Nibbler

One humorous incident involved the game's high score board. As was common at the time the default high score board consisted of the designers' initials. By tradition initials were listed in the order in which people contributed to the game. Joe Ulowetz listed his initials first but put those of his girlfriend (now his wife) second, though she had nothing to do with designing the game. As if that weren't enough, Ulowetz added an easter egg. Get a high score and enter his initials and you receive the message "You have the same initials as my Author." Enter his girlfriend's initials and you get "You have the same initials as my Angel". The bucking of tradition and the sappiness of the message demanded a response so one of the game's programmers altered the EPROMs on some versions of the games to replace the word "Angel" with something a bit more humorous.

McVey's first 6 attempts at the world record were unsuccessful (during one he passed out). On January 15, 1984 he tried again. With Pac-Man champions Chris Ayra and Billy Mitchell cheering him on, he began the arduous journey to the mythical billion-point barrier. Then, around the time he reached 800 million points, a friend burst into Twin Galaxies holding a certified letter claiming that someone else had reached not just one billion but TWO billion points. McVey was heartbroken. Until someone notice that the two billion point game was actually accomplished by a two-man teams who switched on an off. Reinvigorated, McVey pressed on. As he approached the record, the crowds grew. The local TV station sent a camera crew over to capture the event live and the glare from their camera was blinding. When he reached 990 million points, McVey had just six men left. Finally, at 10:45 AM on January 17th (he'd started at 2:00 PM on the 15th) McVey reached his goal and walked away from the machine after almost 45 hours.

He then made the short walk to his house, sat on the edge his bed and told him mother he was hungry. While mom made him macaroni and cheese, Tim, exhausted, fell backward onto his bed and fell asleep. When he woke up and asked for his mac and cheese, his mother told him he could have it but it might be cold – though it had been warm two days ago when she made it. McVey had slept for 38 hours straight. Unfazed, he heated up his victory dinner, wolfed it down, and headed back to Twin Galaxies. For his record smashing efforts, McVey got a free Nibbler game and a key to the city of Ottumwa, which later declared January 28th Tim McVey Day. The Nibbler game did not last long. McVey soon found himself out of money and wanting to play games. As he looked for a source of ready cash, his eyes fell on his Nibbler machine. Since the last thing he wanted to do was play more Nibbler, and the machine was doing nothing more than taking up space, he sold it to a rival arcade down the street from Twin Galaxies – according to Walter Day for about $50 worth of tokens - a decision he now regrets. McVey’s record did not last long either. In September 1984, an Italian teenager named Enrico Zanetti played the game for 40 hours and 15 minutes in a bar in Legnano, Italy on the outskirts of Milan, scoring 1,001,073,840 points. Zanetti had first read about McVey’s records in the pages of VideoGiochi ("VideoGames"), the leading Italian video game magazine of the time. In April 1984, the magazine had announced the formation of the AIVA (Italian Organization of Video Athletes) and began printing national record scores for various games. The next month, the magazine printed a chart of Twin Galaxies’ scores where McVey’s billion point Nibbler marathon stood in stark contrast to the then-Italian record score of 350 million points. Fascinated, the 15-year-old Zanetti decided to try and break the Italian record. After honing his skills at Chip’s Game arcade in Legnano, he switched to a bar called Bar Grillo, where the joystick was more to his liking. By late September, Zanetti was ready for his shot at glory. After the bar owner agreed to let him play on a Monday, when the bar would be closed, Zanetti started his assault on September 27. By Tuesday morning, he had passed the Italian record, which by then stood at 577 million. Still going strong, he decided to press on and try for the world record. By Tuesday afternoon, word had begun to spread and between 8:30 and 9:30 that evening, with Zaenetti’s score at over 900 million points, the news crews began to arrive. At 12:33 on Wednesday morning, Zanetti finally called it quits with 38 lives remaining. While Zanetti’s record drew a good deal of coverage in Italy, it went largely unnoticed in the US. Twin Galaxies could not verify it and McVey claims he did not hear about it until years later – though Twin Galaxies apparently did later list Zanetti’s record for some time before taking it down. As for Zanetti, in October 1984, he participated in a Heineken-sponsored Nibbler challenge in Turin, but finished second. He then retired from competitive video gaming for good, turning instead to ping pong, karate, and kick boxing.

McVey too went on with his life, but by 2008, his interest in Nibbler had been rekindled. By then, he knew about Zanetti’s score and was ready to establish himself once and for all as the undisputed Nibbler champion of the world. With Zanetti in retirement, however, he needed another opponent. He found one in Dwayne Richard, a Canadian multigame expert whose video game career had started around 1986. At the 2009 MAGFest 7 music and games tournament, McVey and Richard squared off in an attempt to set a definitive Nibbler record. Halfway to the billion-point mark, however, Richard’s game froze up. McVey continued for several hours, but when it became apparent he did not have enough men in reserve to break the record, he walked away from his game. Then, on February 14, 2009, playing in his own home, Richard set a new record, scoring 1,004,000,000 points in just 35 hours and 4 minutes – almost ten hours fewer than McVey had taken in 1983. The speed with which Richard achieved his record seemed too good to be true. And it was. When tapes of Richard’s and McVey’s gameplay were compared, Richard’s machine was observed to redraw the board much faster between rounds, shaving precious seconds off his time. When the discrepancy was pointed out to Richard, he voluntarily withdrew his score. While some suspected foul play, the difference was eventually traced to a single balky connector on the microprocessor on Richard’s machine. On July 31, 2011, McVey and Zanetti’s record was beat for real when Rick Carter scored 1,022,222,360 points at Richie Knucklez arcade in Flemington New Jersey. Carter’s unequivocal breaking of his record breathed new life into McVey and on Christmas day 2011, he settled the matter by scoring 1,041,767,060 points in his Iowa home. Meanwhile, on that same day, Elijah Hayter of Portland, Oregon, the son of Dig Dug world champion Ken House, was setting a new marathon record on Track and Field. In the summer of 2012 Hayter, set a new Nibbler Record surpassing Mcvey’s total by just over a million points. Then in November 2012, Rick Carter scored 1.2 billion points at Logan Hardware in Chicago to set a new Nibbler record that still stands as of this writing.

(for more on the Nibbler high score, see the following links:

http://www.retrouprising.com/index.php?pid=enrico_zanetti; http://www.retrouprising.com/index.php?pid=elijah-hayter

and the recently-released documentary Man Vs. Snake - from which much of the above information was taken)

Back to Rock-Ola

Life at Rock-Ola

Other floors were littered with 45s that were used to test the jukeboxes' loading mechanism. The designers would play kick Frisbee with a goalie at each end of the hallway.

While they may not have been video game veterans, Rock-Ola's video game team didn't lack design skills. Jaugilas, Ropp, and Bak went on to design a number of successful home games at Action Graphics and Ropp became a top pinball game designer. The Rock-Ola designers, however, faced limitations that their cross-town colleagues did not.

Rock-Ola didn't last long in the video game world. By the time Ropp was hired in 1982 the company was under a hiring freeze and beginning to feel the pinch from the coming crash. In addition the company's overall sales were in sharp decline. One VP tried to initiate the same bundling strategies they'd used with vending machines by requiring distributors to buy a certain number of jukeboxes for each video game they bought. Instead, the distributors bought neither and jukeboxes sales to 75 a week (from 750 not too many years before).

|

| Nibbler flyer |

Rock-Ola's biggest hit

was Nibbler, designed and programmed by Joe Ulowetz

with support from John Jaugilas and Lonnie Ropp. The game put the player in

control of a snake that moved through a maze eating the food strewn about the

floor. Each bite caused the snake to grow in length and completing a maze

required both speed (since the player couldn't stop moving) and planning. Nibbler

had its roots in a few other games. Gremlin's much-copied Blockade introduced the idea of a player controlling a snake that

got longer as the game progressed. The TRS-80 game Worm added the idea of the snake growing only when it ate

something. Unusually for a game of the time, Nibbler featured no opponents or enemies, and idea that appealed to

designer Joe Ulowetz.

[John Jaugilas] The main reason for Nibbler

was that Joe Ulowetz was primarily a pacifist and wanted to have a game where

you could only hurt yourself, not anyone else. This is what made the combo of

me and Joe so strange as I was a big action, shoot-'em-up game fan and he

wanted a game his girlfriend Mary (initials MRS) would like. Anyway, Joe did

the main game logic, I worked on the maze designs and overall gameplay (I was a

good gamer and Joe could barely make it past wave 5). Strange combo the two of

us, but it worked out. .

The game is probably most famous, however, for being the first game to

feature a 9-digit score. To turn over Nibbler

a player had to score a whopping billion points.

[John Jaugilas] The billion point thing was Uncle Larry's idea. As he said,

"points are free, but quarters are hard to come by." Larry's philosophy

was to give points for anything positive. You moved a joystick, great, 50

points. You ate a nuclear nugget, wonderful 1,000 pts. He noted that on pinball

games the last one or two 0's were just painted on to make the score look

higher, but heck bits were free, so give away points and make someone feel good

about a higher score. Heck, they might even put in another quarter so they

could get an even higher score.

Sidebar - Tom

Asaki, Tim McVey and the Quest for the Billion Point Score

Soon after its introduction, gamers all over the country

were playing the game in hopes of being the first to reach the magical number and

win nationwide acclaim. Attention soon turned to Ottumwa, Iowa’s famed Twin

Galaxies arcade where a teen named Tom Asaki had become the favorite. Asaki was

already well-known in the gaming community, having been part of the three man "Bozeman

Think Tank" that developed the Ms.

Pac-Man grouping strategy back in 1982.

. As Asaki mounted his assault national wire services

began reporting on his quest. Rock-Ola responded by offering a free Nibbler machine to the person who first

reached the magic number. Asaki never made it – failing in four well-publicized

attempts. In the first, he scored 838 million points in forty hours before

losing his last man. The next try ended after 707 million points when Tom

exceeded the “limit” of 127 free men. The machine would eliminate all of your

free men if you reached 128 and knowing exactly how many men you had was crucial. The free man limit did provide marathon players with a measure

of relief since they could leave the game when they accumulated 127 men and

take a break while snake after snake died (which took enough time for the

player to take a crucial bio-break). Asaki's third game ended when the game’s

joystick broke after 793 million points. The final attempt proved something of

an anti-climax when the game broke after just 120 million points. Meanwhile,

another Twin Galaxies regular was mounting a challenge of his own.

Tim McVey got interested in Nibbler when he came into Twin Galaxies one day and saw throngs of

cheering spectators gathered around Tom Asaki as he made one of his world

record attempts. The 17-year-old McVey had never heard of anyone getting such a

high score or seen such excitement over a video game. Though he had

never played the game before, McVey quickly became the best Nibbler player in town other than Tom

Asaki. The two struck up a fast friendship and began sharing strategies

and comparing notes about the game.

McVey's first 6 attempts at the world record were unsuccessful (during one he passed out). On January 15, 1984 he tried again. With Pac-Man champions Chris Ayra and Billy Mitchell cheering him on, he began the arduous journey to the mythical billion-point barrier. Then, around the time he reached 800 million points, a friend burst into Twin Galaxies holding a certified letter claiming that someone else had reached not just one billion but TWO billion points. McVey was heartbroken. Until someone notice that the two billion point game was actually accomplished by a two-man teams who switched on an off. Reinvigorated, McVey pressed on. As he approached the record, the crowds grew. The local TV station sent a camera crew over to capture the event live and the glare from their camera was blinding. When he reached 990 million points, McVey had just six men left. Finally, at 10:45 AM on January 17th (he'd started at 2:00 PM on the 15th) McVey reached his goal and walked away from the machine after almost 45 hours.

He then made the short walk to his house, sat on the edge his bed and told him mother he was hungry. While mom made him macaroni and cheese, Tim, exhausted, fell backward onto his bed and fell asleep. When he woke up and asked for his mac and cheese, his mother told him he could have it but it might be cold – though it had been warm two days ago when she made it. McVey had slept for 38 hours straight. Unfazed, he heated up his victory dinner, wolfed it down, and headed back to Twin Galaxies. For his record smashing efforts, McVey got a free Nibbler game and a key to the city of Ottumwa, which later declared January 28th Tim McVey Day. The Nibbler game did not last long. McVey soon found himself out of money and wanting to play games. As he looked for a source of ready cash, his eyes fell on his Nibbler machine. Since the last thing he wanted to do was play more Nibbler, and the machine was doing nothing more than taking up space, he sold it to a rival arcade down the street from Twin Galaxies – according to Walter Day for about $50 worth of tokens - a decision he now regrets. McVey’s record did not last long either. In September 1984, an Italian teenager named Enrico Zanetti played the game for 40 hours and 15 minutes in a bar in Legnano, Italy on the outskirts of Milan, scoring 1,001,073,840 points. Zanetti had first read about McVey’s records in the pages of VideoGiochi ("VideoGames"), the leading Italian video game magazine of the time. In April 1984, the magazine had announced the formation of the AIVA (Italian Organization of Video Athletes) and began printing national record scores for various games. The next month, the magazine printed a chart of Twin Galaxies’ scores where McVey’s billion point Nibbler marathon stood in stark contrast to the then-Italian record score of 350 million points. Fascinated, the 15-year-old Zanetti decided to try and break the Italian record. After honing his skills at Chip’s Game arcade in Legnano, he switched to a bar called Bar Grillo, where the joystick was more to his liking. By late September, Zanetti was ready for his shot at glory. After the bar owner agreed to let him play on a Monday, when the bar would be closed, Zanetti started his assault on September 27. By Tuesday morning, he had passed the Italian record, which by then stood at 577 million. Still going strong, he decided to press on and try for the world record. By Tuesday afternoon, word had begun to spread and between 8:30 and 9:30 that evening, with Zaenetti’s score at over 900 million points, the news crews began to arrive. At 12:33 on Wednesday morning, Zanetti finally called it quits with 38 lives remaining. While Zanetti’s record drew a good deal of coverage in Italy, it went largely unnoticed in the US. Twin Galaxies could not verify it and McVey claims he did not hear about it until years later – though Twin Galaxies apparently did later list Zanetti’s record for some time before taking it down. As for Zanetti, in October 1984, he participated in a Heineken-sponsored Nibbler challenge in Turin, but finished second. He then retired from competitive video gaming for good, turning instead to ping pong, karate, and kick boxing.

McVey too went on with his life, but by 2008, his interest in Nibbler had been rekindled. By then, he knew about Zanetti’s score and was ready to establish himself once and for all as the undisputed Nibbler champion of the world. With Zanetti in retirement, however, he needed another opponent. He found one in Dwayne Richard, a Canadian multigame expert whose video game career had started around 1986. At the 2009 MAGFest 7 music and games tournament, McVey and Richard squared off in an attempt to set a definitive Nibbler record. Halfway to the billion-point mark, however, Richard’s game froze up. McVey continued for several hours, but when it became apparent he did not have enough men in reserve to break the record, he walked away from his game. Then, on February 14, 2009, playing in his own home, Richard set a new record, scoring 1,004,000,000 points in just 35 hours and 4 minutes – almost ten hours fewer than McVey had taken in 1983. The speed with which Richard achieved his record seemed too good to be true. And it was. When tapes of Richard’s and McVey’s gameplay were compared, Richard’s machine was observed to redraw the board much faster between rounds, shaving precious seconds off his time. When the discrepancy was pointed out to Richard, he voluntarily withdrew his score. While some suspected foul play, the difference was eventually traced to a single balky connector on the microprocessor on Richard’s machine. On July 31, 2011, McVey and Zanetti’s record was beat for real when Rick Carter scored 1,022,222,360 points at Richie Knucklez arcade in Flemington New Jersey. Carter’s unequivocal breaking of his record breathed new life into McVey and on Christmas day 2011, he settled the matter by scoring 1,041,767,060 points in his Iowa home. Meanwhile, on that same day, Elijah Hayter of Portland, Oregon, the son of Dig Dug world champion Ken House, was setting a new marathon record on Track and Field. In the summer of 2012 Hayter, set a new Nibbler Record surpassing Mcvey’s total by just over a million points. Then in November 2012, Rick Carter scored 1.2 billion points at Logan Hardware in Chicago to set a new Nibbler record that still stands as of this writing.

(for more on the Nibbler high score, see the following links:

http://www.retrouprising.com/index.php?pid=enrico_zanetti; http://www.retrouprising.com/index.php?pid=elijah-hayter

and the recently-released documentary Man Vs. Snake - from which much of the above information was taken)

Rock-Ola

itself didn't find out about the Asaki and McVey's quest until after Asaki's

second failed attempt.

[Mike Perkins] One day I

got a telephone call from someone at an arcade in some obscure place. The

person was jabbering about an marathon session that ended unexpectedly and I

suspected a hardware problem. The person said the number of lives when the game

reset was 126 or 127, they weren’t sure which. I was always hearing about

VectorBeam games that reset due to a particular way the game processor was

designed (called a frame-out), and so my mind was reeling at the number of

various possibilities for the reset. But the number of Nibbler lives at which

the game reset had an auspicious, technical sound to it: 127 is the modulo of 7

bits, minus one. I had no idea how the code was written, but modulo numbers

like that strike terror (or strike gold) in the heart of anyone who is left to

debug code when everyone else is gone.

[Asaki] had just gained

another life when the game reset, so I started looking at the life calculation

and end-of-game logic. It turned out that Joe’s code was written such that the

upper bit of the byte containing the number of lives was a carry bit (or borrow

bit for subtractions). Thus, only seven bits were available for the number of

lives, so 127 was the max. I changed the code to limit the max lives to 127. I

burned new EPROMs, tested it, and sent them Fed-Ex to wherever the arcade was

located. I never heard anything else, except years later when someone told me

about Nibbler and McVey’s marathon session.

|

| The Rock-Ola factory at 800 North Kedzie, Chicago |

The video game designers at Rock-Ola a

lot of ways to blow off steam. The Rock-Ola factory was huge and ancient, with

piles of unused equipment lying around. Running underneath the parking lot was a

rat-infested rifle range (a relic of the days making the M1 Carbine).

[Mike Perkins]

There were three other buildings in the compound, smaller, and mostly

unoccupied at the time. One of them was remote building across the parking lot

that used to generate power before during World War II and at night when the

plant was mostly shut down, they would sell power back to the power company.

…The plant also used to make, among other things, rocker arms for aircraft and tank engines. Some of the punch presses, still in use in 1982 for making vending machines, were 25 feet tall and had flywheels weighing probably 10 tons.

In that whole big building, there were only three elevators; one for office personnel, and two for the factory. Even though waiting for elevators was a major occupation of many factory people, anyone in a blue shirt or with grease on their pants knew better than to get on the office elevator.

One of the factory elevators was just large enough for a couple of can vending machines on it. The other was a personnel elevator for sending small parts between floors. The problem was that production of can vendors was done on two different floors. If you can imagine the elevator bottleneck trying to move 300 vending machines from the second floor to the fourth and then from the fourth to the first for crating and storage, well, it was a logistical mess.

The interesting spot in the whole place was the jukebox demo room, very well set up to resemble a darkly-lit, black-carpeted, leather couched cocktail lounge. I spent a lot of time in there.

…The plant also used to make, among other things, rocker arms for aircraft and tank engines. Some of the punch presses, still in use in 1982 for making vending machines, were 25 feet tall and had flywheels weighing probably 10 tons.

In that whole big building, there were only three elevators; one for office personnel, and two for the factory. Even though waiting for elevators was a major occupation of many factory people, anyone in a blue shirt or with grease on their pants knew better than to get on the office elevator.

One of the factory elevators was just large enough for a couple of can vending machines on it. The other was a personnel elevator for sending small parts between floors. The problem was that production of can vendors was done on two different floors. If you can imagine the elevator bottleneck trying to move 300 vending machines from the second floor to the fourth and then from the fourth to the first for crating and storage, well, it was a logistical mess.

The interesting spot in the whole place was the jukebox demo room, very well set up to resemble a darkly-lit, black-carpeted, leather couched cocktail lounge. I spent a lot of time in there.

Other floors were littered with 45s that were used to test the jukeboxes' loading mechanism. The designers would play kick Frisbee with a goalie at each end of the hallway.

[John

Jaugilas] They had the huge steel crates of test scratched up 45s. They also

had these crates of old transformers. Rock-Ola was a huge, primarily empty

factory. Only about 10 % of the place was occupied. So when we'd come back from

the cafeteria after lunch we'd find some transformers and see how far we could shot-put

them down the hallways. That got boring after a while so we found that you

could hurl a 45 a long way if you flung it just right. Well our offices had a

railroad track outside the big factory windows and on the other side of the

tracks was some warehouse with one of those big curved tarpaper roofs. So after

lunch we would open up a window wide and see if we could fling a 45 out the

window, across the train tracks and get it to turn vertical and stick into the

tar roof across the way. It wasn't easy. That was at least 100 to 200 feet.

Often with the wind up you'd fling a 45 into the window frame and it would

shatter. There was a 10 ft. pile of broken 45s under one or two of the prime

flinging windows.

Antics like this may be why other employees dubbed the video game

section the "rubber rooms" (because, as Jaugilas says "they

thought we were bouncing-off-the-walls crazy").

[Mike

Perkins] At

one point I got Connie [the company nurse] to come measure our blood pressure

and heart rate as a “scientific” data point of game excitement. I did it mostly

as a hedge against the mid-project doldrums, just to have a woman sit with us a

while so the guy could strut a little bit and be peacocks.

It wasn't all fun

and games, however. 10-14 hour days were not uncommon and programmers sometimes

didn't leave until two in the morning. The primitive (by modern standards)

tools at the time didn't help.

[Lonnie Ropp] We had these huge floppies that you

would compile your code and link on, then burn EPROMS. To do all of that…would

take half a day…and that's every change that you made. So basically what we

would do is we'd go home at night - because it's video games and you love what you're doing - and write a bunch of code. [Then] come to

work. Type all that stuff in, compile it, burn an EPROM and it's time for

lunch.

And then You did some more writing and hopefully before you left that night you went through one more iteration. So basically we had…two code iterations a day. That's amazing when you look at these games where you get to see the results of your work and then make additions or modifications of corrections.

And then You did some more writing and hopefully before you left that night you went through one more iteration. So basically we had…two code iterations a day. That's amazing when you look at these games where you get to see the results of your work and then make additions or modifications of corrections.

Hard work or not, Rock-Ola never

really had a major hit to match those of crosstown rivals Williams, Gottlieb,

or Bally.

[Mike Perkins] Our games always had one or two followers, but never enough to shill

the game to the point of reaching success past the game designed by real game

designers, which we were not. We were technical guys turned, by circumstances,

into fledgling game designers. But our ideas and sophistication was never a

match for the pinball game designers who waltzed into video games with their

understanding of what makes people excited about playing arcade games…The

problem was that I, and Rock-Ola in general, was always one game-cycle behind,

if not two.

While they may not have been video game veterans, Rock-Ola's video game team didn't lack design skills. Jaugilas, Ropp, and Bak went on to design a number of successful home games at Action Graphics and Ropp became a top pinball game designer. The Rock-Ola designers, however, faced limitations that their cross-town colleagues did not.

[John

Jaugilas] We had good design skills but Rock-ola was

cheap. While other companies like Williams and Bally would design and build new

boards with new capabilities Rock-ola wanted us to recycle overrun game boards

from bad video games. Rather than designing and building a good game capability

from scratch using good graphics processors, they would find old bad games

(that is why Rock-ola had some many cheesy bad games from overseas) buy up the

whole stock of game board cheaply, put a few on the market and then have us try

to re-program the boards with a better game. We were a game board recycling

shop. That fact that we could get games like Demon or Nibbler made

out of some old reject game board made our jobs a lot harder than someone working

at Williams or Bally that were working on game boards that were one or two

generations ahead of what we were given to work with.

The game developers at Rock-ola had an arm and leg tied behind their backs and were told to run the race and finish in the top 5. They made plenty of money that way. that is also why some of us were successful working on home game systems after Rock-ola. At least we got current technology to work with.

The game developers at Rock-ola had an arm and leg tied behind their backs and were told to run the race and finish in the top 5. They made plenty of money that way. that is also why some of us were successful working on home game systems after Rock-ola. At least we got current technology to work with.

Rock-Ola didn't last long in the video game world. By the time Ropp was hired in 1982 the company was under a hiring freeze and beginning to feel the pinch from the coming crash. In addition the company's overall sales were in sharp decline. One VP tried to initiate the same bundling strategies they'd used with vending machines by requiring distributors to buy a certain number of jukeboxes for each video game they bought. Instead, the distributors bought neither and jukeboxes sales to 75 a week (from 750 not too many years before).

[Mike Perkins] The first indication to me was the flagging jukebox sales, because of

them being the staple for Rock-Ola, with AMI eating our lunch, not just

technically, but with a fresh sales approach. When video games came along, the

future looked brighter to me, personally, because of the technical challenge

and fun it presented. So for a couple of years, I had blinders on, and didn’t

pay much attention to the business aspect – we all kept getting paychecks and

things were fine. We played kick Frisbee, shot-putted transformers, threw 45s

onto tar-encrusted roofs across a bed of train tracks, and had some marvelously-fun

lunches at places like Bishop’s Chili

and Jimmy’s Red Hots. We were kids

doing kid-things. But when our paychecks one week dropped to 80% of what they

had been, the fun was over, and the writing was on the wall.

Before long the game developers began

to scatter to the winds, Rock-Ola went to a 4-day workweek and in 1983 the

company shut down its video game division. Lonnie Ropp went to Entertainment

Sciences where he worked on Bouncer

before returning to Chicago. John Jaugilas and Joe Bak went to Action Graphics,

where they developed home and computer games (along with Richard and Elaine

Ditton from Marvin Glass/Midway and Dave Thiel from Gottlieb). Jaugilas, Bak,

and Ropp (along with the Dittons) later formed Semaphore Systems. Jaugilas and Bak

then left the coin-op game industry, but Ropp became a pinball designer and to

date has worked on 61 games (tied for 15th on the all-time list).

As for Rock-Ola, the company eventually moved to nearby (and much safer) Addison. David Rockola continued to show up for work each day into his 80s. In 1992 the company's jukebox assets were sold to Glenn Streeter of the Antique Apparatus Company who moved the company to Torrance, California where it still exists today. David Rockola died in 1993 at the age of 96.

As for Rock-Ola, the company eventually moved to nearby (and much safer) Addison. David Rockola continued to show up for work each day into his 80s. In 1992 the company's jukebox assets were sold to Glenn Streeter of the Antique Apparatus Company who moved the company to Torrance, California where it still exists today. David Rockola died in 1993 at the age of 96.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)