The pop song is the 1980 novelty hit "Space Invaders"

by Uncle Vic, one of a number of songs related to the game Others include “Disco

Space Invaders” by Funny Stuff, released in 1979 on Elbon records; “Space

Invaders”, another 1979 song by the Australian band Player 1/Playback and The Pretenders

1979 instrumental “Space Invaders”. Those songs will have to wait for another

day. Today, we’re talking about Uncle Vic. Before we get started, here's a link to a YouTube video of the song

Uncle Vic was Victor

Earl Blecman, a 27-year-old musician, nightclub owner, and DJ for WGCL in

Cleveland. Blecman's music career has started in Elyria, Ohio in1965 when he

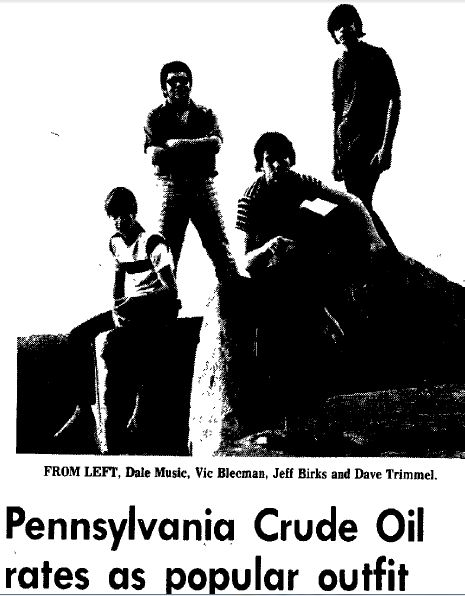

formed a band called The Cavemen with three junior high school classmates. The

band continued through Blecman's high school and community college years under various names,

including Flight, Pennsylvania Crude Oil, Revolver, and Izz, playing at various

local clubs like Pickle Bill's and Big Dick's (in 1971, Izz shared a bill with

Black Sabbath). Vic would often inject his oddball sense of humor into the

band's sets and before long he was doing more joking than playing. He

eventually landed a job as a disk jockey in Elyria, while performing

disco-themed comedy as "The Fantastic and Intergalactic Uncle Vic" at

Elyria's Rathskellar Club (where, in 1976, he tried to set a Guinness World

Record for continuous joke-telling). In January, 1977 he opened an adults-only disco

club in Elyria called Uncle Vic's Night Club along with two partners.

Meanwhile, Blecman had patented a keyboard instrument called the "talking

machine" that made use of recorded sounds. In June of 1978, he attended a

Chicago trade show trying to find a manufacturer for his device when he ran

into the Bradley Brothers, an English trio who had invented another keyboard

instrument called the Novatron and signed up to distribute the machines in

North America. He also recorded a record called "Baby, Now That I've Found

You", scoring a minor local hit.  |

| Uncle Vic in his high school days (from Elyria Chronicle, 1970) |

|

| From Elyria Chronicle, 1969 |

|

| Izz - From Elyria Chronicle, 1971 |

The idea to create a novelty record based on a video game

came around May of 1980 when Vic was playing a show at his night club and

noticed that his audience was distracted by the blooping and bleeping of a Space Invaders machine in the back

room. Annoyed, Vic's band began playing along with the game, imitating its

sounds. The audience loved it and Blecman soon decided to record a song based

on the game.

[Vic

Blecman] That's where I saw people line up for the machine. Cheering and

yelling and completely lost in playing. So were the watchers. Then I read about

the space machines in magazines and heard about tournaments in Europe, South

America, America, and Japan. It's international. I decided something that

popular deserved to have a song written about it. <Jane Scott, "'Space

Invaders' 45 could blow your mind', Cleveland

Plain Dealer, July 4, 1980>

Then Blecman found out that the Pretenders had included a

song called “Space Invaders” on their debut album and almost dropped the idea,

until he found out that the song had nothing to do with the game. Blecman then assembled

a group to record his song (which he claims he wrote in his bathroom in about

half an hour) and recorded it at 3 A.M. at Kirk Yano's After Dark recording

studio in five hours at a cost of $4,000. Backing up Blecman (who played bass

and sang vocals) were Kirk Yano on guitar, Jose Ortiz on drums, and Pete Tokar (who

duplicated the machine's sounds on a synthesizer[1]).

"Space Invaders" opened with the lines

"Well, there it is in the corner of the bar / I tried to run, but I didn't

get far / Those weird little men; I

blow 'em away / Id' sell my mom for a chance to play", followed by the

song's hook, sung in an alien voice: "He's hooked, he's hooked, his brain

is cooked". The chorus featured the words "Space Invaders" sung

over and over as the synthesized sounds of the game played in the background.

As the song ended, it got faster and faster (like its coin-op inspiration)

before ending with a loud explosion.

Blecman pressed 2,000 copies of the record on his own

Partay Label and negotiated with Progress Records to distribute them, mailing

copies to a number of radio stations. The song quickly became the most

requested song on Cleveland area stations (though Blecman, who was also a disk

jockey at Cleveland’s WGCL, wasn't allowed to play it on his own show due to

FCC regulations) and also became a hit in St. Petersburg and Tampa, Florida.

Blecman then struck a deal with Prelude Records, who'd also released the

novelty classics "Ahab the Arab" by Ray Stevens and "My

Ding-A-Ling" (shamefully, Chuck

Berry's biggest hit) to release "Space Invaders" nationally as a single

(b/w "Ode to Slim", an homage to Slim Whitman). While "Space

Invaders" failed to crack the

national charts, it became a Dr. Demento staple and, for those who heard it, a

fondly-remembered relic of the golden age of video games. Two years later, Uncle

Vic tried again with another video game song based on Pac-Man titled "It Won't Beat Me". The song went nowhere.

Space

Invaders

©1980 by Uncle Vic

©1980 by Uncle Vic

Well, there it is in the corner of the bar

I tried to run, but I didn't get far

Those weird little men; I blow 'em away

I'd sell my mom for a chance to play

(He's hooked, he's hooked. His brain is cooked.

He's hooked, he's hooked. His brain is cooked.)

They start off slow, but they don't play clean

It's tricky and low; it's a mean machine

There's lots of them and one of you

When the walls are gone, they'll get to you

(He's hooked, he's hooked. His brain is cooked.

He's hooked, he's hooked. His brain is cooked.)

Space invaders (game sounds)

Space invaders

Space invaders

Space invaders

Faster and faster all the time

An hour of this will blow your mind

Gotta get them before they get you

and you'll be broke before you're through

(He's hooked, he's hooked. His brain is cooked.

He's hooked, he's hooked. His brain is cooked.)

As the gang looks over your shoulder in awe

They don't believe what they just saw

You slid to the left and slid to the right

You're the Space Invaders king tonight

(He's hooked, he's hooked. His brain is cooked.

He's hooked, he's hooked. His brain is cooked.)

Space invaders (game sounds)

Space invaders

Space invaders

Space invaders

A feeling of power comes over your hand

Row by row, you're in command

There's one last devil movin' real fast

One single shot (shot noise); got him at last

Space invaders (game sounds)

(Hey, wow, man!)

Space invaders

(I'm gonna get me one of these)

Space invaders

(Yeah!)

Space invaders

(Got it going now!)

Space invaders

(I'm on my fourth row!)

Space invaders

(Gee, they almost got me.)

Space invaders

(We're in trouble now!)

Space invaders

(Oh, wow, really cosmic, man!)

Space invaders (pace quickens)

Space invaders

Space invaders

(Too fast for me, man!)

Space invaders

(high incomprehensible squawking)

Space invaders

Space invaders

Space invaders

Space invaders....

(explosion)

I tried to run, but I didn't get far

Those weird little men; I blow 'em away

I'd sell my mom for a chance to play

(He's hooked, he's hooked. His brain is cooked.

He's hooked, he's hooked. His brain is cooked.)

They start off slow, but they don't play clean

It's tricky and low; it's a mean machine

There's lots of them and one of you

When the walls are gone, they'll get to you

(He's hooked, he's hooked. His brain is cooked.

He's hooked, he's hooked. His brain is cooked.)

Space invaders (game sounds)

Space invaders

Space invaders

Space invaders

Faster and faster all the time

An hour of this will blow your mind

Gotta get them before they get you

and you'll be broke before you're through

(He's hooked, he's hooked. His brain is cooked.

He's hooked, he's hooked. His brain is cooked.)

As the gang looks over your shoulder in awe

They don't believe what they just saw

You slid to the left and slid to the right

You're the Space Invaders king tonight

(He's hooked, he's hooked. His brain is cooked.

He's hooked, he's hooked. His brain is cooked.)

Space invaders (game sounds)

Space invaders

Space invaders

Space invaders

A feeling of power comes over your hand

Row by row, you're in command

There's one last devil movin' real fast

One single shot (shot noise); got him at last

Space invaders (game sounds)

(Hey, wow, man!)

Space invaders

(I'm gonna get me one of these)

Space invaders

(Yeah!)

Space invaders

(Got it going now!)

Space invaders

(I'm on my fourth row!)

Space invaders

(Gee, they almost got me.)

Space invaders

(We're in trouble now!)

Space invaders

(Oh, wow, really cosmic, man!)

Space invaders (pace quickens)

Space invaders

Space invaders

(Too fast for me, man!)

Space invaders

(high incomprehensible squawking)

Space invaders

Space invaders

Space invaders

Space invaders....

(explosion)

|

| Uncle Vic in 2008 |

Nightfall – No Quarter

While Uncle Vic’s hit is far from well-known, I’m sure a number of readers will

remember it. I can’t say the same for my next bit of radio ephemera. Actually,

I’ve already written about this one, but it was way back in the second post I

ever did, so some of you may have missed it (for those who didn’t, this part

will largely be a repeat of my earlier post).

This

one isn’t a song, but a bit of radio drama, an art form that has become

increasingly rare, but was a bit more common back in the 1970s and 1980s

(remember the NPR production of Star Wars?).

This one, however, wasn’t an NPR program. In fact, it wasn’t even American. It

was an episode of Nightfall, a Canadian

horror anthology series broadcast on CBC from July, 1980 to May, 1983. I am actually

a longtime fan of “OTR” (old time radio), particularly radio horror. Nightfall isn’t OTR, but it is one of

the finest radio horror anthologies ever produced, IMO.

Unfortunately,

the subject of this post wasn’t one of the program’s finest efforts (though I

enjoyed it thoroughly anyway). . It was, however, a rare (if not unique) example

of a video-game-themed radio drama. The episode I’m talking about is “No Quarter”,

which aired on March 4, 1983. You can download it from many places on the web. Here

is a link to an internet archive page with “No Quarter” along with most of

the other episodes of the series (if you have any interest in horror or radio

drama, check out some of the other episodes)

"No

Quarter” tells the story of Paul Weaver, a poor shlub who becomes obsessed with

video games after playing Donkey Kong

while waiting for a delayed flight at the Vancouver Airport. On a drive home from dinner, he and his wife

get into an argument over the time he's spending on the games. She is concerned

that the games promote anti-social behavior in violence. He replies that the

games are educational ("The Defense Department uses Armor Attack as a simulator for tank training." he argues).

After he loses his job when he misses an important meeting because he's busy

playing Defender ("It you want

to beat Defender, don't use the smart bomb in hyperspace”, the arcade owner

dubiously tells him), his wife launches a public crusade against video games.

One day, Paul gets a mysterious package containing an ultra-advanced arcade

game called Death Ship in which an

intergalactic slave laborer tries to escape his "Robotron masters". Paul

begins playing the game, drawn in by its incredible graphics, voice synthesis,

and hyper realistic action. As his score mounts, the game becomes even more

lifelike, until it eventually becomes a little too realistic (you’ll

have to listen yourself to find out how it ends). Almost unknown today, the

episode contains a host of video game references. Death Ship’s digitized

voice intones "coin detected in pocket" ala Berzerk. At one point, the arcade owner tells Paul "Some

computer science student in Buffalo blew the brains out of a Pac-Man. You know

it only stores six figures. Well, he turned it over three times and the screen

split the maze on one side and this electronic gibberish on the other."

[1] Jane Scott, “’Space Invaders’ 45 could

blow your mind”, Cleveland Plain Dealer,

July 4, 1980. Other sources report that

Blecman played all of the instruments except keyboard.