By late 1979 Allied Leisure Industries

was having a rough time of it. They had lost money in five of their previous

six years and were desperately in need of help. In June of 1979, that help

seemed to have arrived when Allied was purchased by Brighton Products, a

designee company of the Milton Koffman family and their Koffman Group of

Industries conglomerate. The Koffmans had absolutely no knowledge of the

coin-op industry but what they did have was a reputation for turning failing corporations

around. Doing so with Allied would require whole scale changes, and the

Koffmans began to make them. As part of the sale, Allied’s officers and

directors, including Dave Braun, had been forced to resign, with Braun’s

resignation effective immediately (June 1) and the rest effective at the

company’s shareholder’s meeting on August 22. To replace the departed

executives, Allied’s new owners brought in a new team (though Dave Braun stayed

around in a consulting role for 3 years). The team had their work cut out for

them. Allied had a myriad of problems. Perhaps the biggest was the technical

issues that had plagued the company’s games for years.

[Bill Olliges] Allied had a bad name

in the industry because of the quality of the product that they manufactured.

They did a lot of their own metal work internally and none of the operators or

distributors really liked it because it had sharp edges. They also had terrible

reliability.

Reliability wasn’t Allied’s only problem, however. Even the games that did work were often uninspired, with the possible exception of their electromechanical games. The era of electromechancial games, however had passed. Video games had all but taken their place and Allied hadn’t had a truly successful video game since Paddle Battle and Tennis Tourney back in 1973. The company also struggled with financial problems, sluggish management, and production issues. Among the new arrivals was Ken Beuck, who was brought in to head up the company's materials/manufacturing. He arrived to find a mess. One of his first acts was to send out a survey asking what each of the 400+ employees did. Some reported that they just showed up every week to pick up their paychecks. He also found a host of other issues. While the company hadn't seen much in the way of profits they had turned out plenty of different games. The problem was that every time they started a new game, they ordered the materials from scratch, despite the fact that they had a warehouse full of unused parts. In addition, they insisted on making everything themselves - including items like coin doors that could be made more efficiently and cheaply by companies that specialized in them.

Fixing all of these issues wasn’t going to be a quick or easy process. In the meantime Allied somehow had to keep its doors open. Beuck, who had previously worked at Atari, Cinematronics and Vectorbeam, was able to secure a contract to build Space Wars games for the east coast market and to produce some consumer products for Atari. As the year ended, things were still in chaos as Allied. At the 1979 AMOA show, Allied introduced four new video games but only one (Clay Shoot) appears to have made it out the door. It really wasn’t until mid-1980 that things really began to improve.

By then, Allied had recruited a pair of coin-op veterans to head the newly reorganized company and change its focus – Ed Miller and Bill Olliges, president and vice president, respectively, of Taito America. Miller had been Taito America’s president since its earliest days. Olliges had formerly worked at Universal Research Labs and then his own company called American Digital, which was purchased by Taito America in 1978. In early 1979, Olliges served as president of the short-lived Astro Games, an Elk Grove Village manufacturer that had been formed by Robert Anderson and Bob Runte after their Fascination Ltd. went bankrupt. By mid-1979 Astro Games was bankrupt as well and Olliges joined Miller at Taito America. While it appears that Allied Leisure had begun negotiating with the pair in 1979, it seems that they didn’t actually arrive at Allied until spring of 1980[1]. Miller would serve as president of the newy reorganized company and Olliges as Executive VP of Engineering. Other executives would include Milton Kaufman as CEO, Ivan Rothstein (one of the few holdovers from Allied Leisure) as VP of sales, and Thomas Jachimek as VP of Engineering.

Allied, however, didn’t just get a new executive team. In July, the board of directors met in Miami. On July 29th, to mark the company’s new direction and distance themselves from the Allied Leisure name and its “Allied Loser” associations, the board voted to rename the company Centuri. There are differing stories as to how the name came about. As Ken Beuck remembers it he, Miller, and Larry Leppert (an engineer who had formerly worked with Beuck at Vectorbeam and Meadows) decided that since two of them were former Atarians they would now be Centurions. Ed Miller claimed that the name "signified the forward thrust of the company into the 21st century"[2]. The company’s annual reports attribute the idea for changing the name to Milton Koffman and claim that the name itself was chosen by an ad agency.

While the name change was a significant symbolic gesture, a number of more substantial changes were also made. Pinball production was halted and the company began to concentrate almost exclusively on video games (with one notable exception). With the company in such disarray, they were initially unable to produce games of their own so they instead turned to licensing. The first video games bearing the Centuri name were licensed cocktail versions of Cinematronics’ Rip Off (ca July, 1980) and Exidy’s Targ (ca September) [they later made a cocktail version of Gremlin’s Carnival].

Allied Leisure may have had a new name, but Centuri still had to convince skeptical distributors that it wasn’t going to be just more of the same. On September 12-14, they held a lavish promotional meeting at the swanky Doral Country Club and Resort in Miami, even bringing in Peaches and Herb, whose “Reunited” had topped the pop charts in 1979, to provide musical entertainment. After an opening cocktail reception on the 11th, Centuri introduced its new product line to an audience of about 150 distributors. In addition to Rip Off and Targ, they debuted Eagle (probably a licensed version of Nichibutsu’s Moon Cresta) and an in-house designed game called Killer Comet. The big news, however, was the company’s entry into the jukebox market with the Centuri 2001. For a company looking to rebuild confidence in its brand, moving into an area in which they had no previous experience might seem risky, but Centuri believed there was an untapped market waiting to be exploited. Existing jukeboxes used mechanisms that had been developed 25-30 years earlier and were expensive to maintain. Centuri had developed a jukebox using up-to-date technology that they hoped would save on labor costs. In addition, the unit featured a built-in dollar bill changer, a pair of inexpensive “passive radiators” for improved bass response, allowed operators to access bookkeeping totals by entering a 3-digit code, and offered an optional portable printer. To head up their jukebox division, Centuri had brought in John Chapin, former president of Seeburg. Centuri planned to introduce the unit in early 1981, but only time would tell if it would be a success.

|

| Above photos courtesy of Play Meter and RePlay |

All of these changes arrived too late to help in fiscal year 1980 (which ended October 31). While revenues only dropped slightly to $5.9 million, Centuri lost $4.5 million – its worst loss ever. The numbers were a bit deceiving, however. Part of the loss was due to the high restructuring costs, which included increased wages, plus moving and travelling expenses as a result of their recruitment efforts in addition the cost of new products. In addition, with the company preoccupied with reorganization, they had been unable to push enough product out the door to cover expenses. On a positive note, 68% of the company’s revenues had come in the fiscal year’s fourth quarter. Still, in terms of raw numbers, 1980 had not been a good year for Centuri. 1981 would be a different story altogether.

1981

In fiscal year 1981 Centuri underwent one of the most amazing transformations the coin-op world had ever witnessed. Revenues rose from $5.9 million to an astonishing $61.5 million and the company went from losing $4.5 million to a profit of $7.5 million. After selling just 3,730 games in 1980 (and 4,415 the year before that), Centuri sold 31,451 in FY 1981. While the new management team and the restructuring no doubt helped, the biggest reason for the change may have been simply that the company released some stellar games. Centuri introduced six new games during the fiscal year: Eagle, Phoenix, Route 16, Pleaides, Vanguard, and Challenger. Only Challenger was a dud and three of them would be major hits.

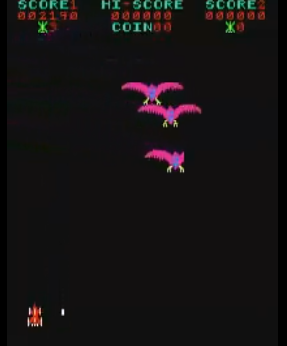

Eagle

First up was Eagle (actually released late in 1980). Eagle was basically the same game as Nichibutsu’s Moon Cresta with slightly different

enemy graphics, and may have been licensed from them[3].

While the game was a vertical shooter in the tradition of Space Invaders and Galaxian,

it illustrated just how far the genre had advanced in the year since Galaxian had appeared on the scene. The

player squared off against four different species of “atomic war birds” that

swooped and looped around the screen. First came mantas – a kind of flying

donut that split in two when hit. Next came mothlike tegors, followed by “giant

prehistoric eagles”, comets, and volars. Every few waves, the player got a

chance to dock with another ship, doubling, then tripling their firepower. Eagle was only a modest hit, generating

$4.55 million in revenue (which probably translates to 2,000-3,000 units).[4]

Compared to Centuri’s recent games, however, it had done quite well indeed. The

next game would do even better.

Phoenix

Like Eagle, Phoenix (January 1981) was a vertical shooter featuring birdlike aliens and also like Eagle, it was a licensed game (in this case from Amstar Electronics). Unlike Eagle, however, Phoenix was a major hit, generating $26 million in sales (probably 13,000-15,000 units), about 43% of Centuri’s total. In terms of revenue in fact, it was probably the company’s biggest hit ever. Phoenix was a five-stage vertical shooter. In the first two waves, the player faced an army of 16 colorful winged aliens. Aliens would occasionally peel off from the formation then tumble towards the player before flying back to join the group (during which time they were worth a hefty 200 points). The next two rounds featured two lines of eggs that grew into giant birds then attacked in wide sweeping arcs. Hitting a bird’s body destroyed it while a glancing blow literally “winged” it, clipping off one of its appendages. Finally, the player faced a huge alien mother ship with an armada of space birds protecting it. The player had to slowly chip a hole through the ship’s hull and a moving purple band to reach the alien boss within. In addition to lasers, the player had a shield that could protect them for a limited time. The ultimate source of the game, and its original name, are a bit unclear. Centuri licensed it from Amstar Electronics. Amstar was relatively new. In early 1980 they had purchased Mirco’s Mirco Games division, which was then primarily producing pseudo-gambling games like Super Twenty One and Hold and Draw Poker. While Amstar initially continued to produce these games, they soon struck a licensing deal with Nichibutsu for a cocktail version of Moon Cresta. In November 1980, RePlay reported that they were developing a “space game” of their own, but also looking to license a game from another manufacturer. Both games were being field-tested in Japan. It appears that Phoneix may have been licensed from Hiraoka & Co. Ltd. (from whom Centuri later licesned Round-Up), but this is unclear[5]. As for the name, Ken Beuck recalls that Centuri renamed the game Phoenix in hopes that it would represent the company’s rebirth. All other sources, however, indicate that the game was called Phoenix at the time they licensed it (possibly because Amstar was located in Phoenix, Arizona). If Centuri didn’t choose it, the game’s name was an absolutely uncanny coincidence. The game was the biggest hit the company had had since the disastrous 1974 fire that had laid much of their plant to waste. In other words, Phoenix, like its mythical namesake, was responsible for Allied Leisure’s dramatic rebirth, almost literally from its own ashes.

Pleiades

Again

with the birds. Licensed from the then little-known Japanese manufacturer

Tehkan, Pleiades was yet another

vertical shooter with similarities to Phoenix

(Wikipedia claims it was actually the “official” sequel to the game). The

first two stages were actually quite different from those of Phoenix. The player defended a space

station from a group of Martian invaders that swooped in from the sides of the

screen. If the player did not destroy them quickly, they transformed into creatures

vaguely reminiscent of the walkers from War

of the Worlds and built a wall of bricks above the player. The next two stages

were almost identical to the “giant bird” stages from Phoenix (though given their membranous wings, the enemies may have

been bugs rather than birds). The fifth stage was a mother ship stage, but a

bit different from that of Phoenix. In

the final stage, the player tried to maneuver their way down an ever-narrowing runway,

dodging obstacles and collecting flags as they made their way to a control

base. While it wasn’t nearly as big a hit as its predecessor, Pleiades generated $9.53 million in

sales (probably 4,000-6,000 units).

|

Emilio Estevez - Pleiades hustler (from Nightmares) |

The final game in Centuri’s quartet of 1981 hits was Vanguard (ca October). Like Pleiades it was licensed from a then-obscure Japanese manufacturer (SNK - allegedly their first color game) Giantbomb.com reports that it was actually developed by Tose Software, who later developed games for Nintendo’s Game & Watch and their various home systems (most notably the Dragon Ball series). Unlike Centuri’s earlier games, Vanguard was not a vertical shooter nor did it have anything to do with birds (finally!). Instead, it was one of the finest of the early horizontally scrolling shooters, a kind of souped-up version of Stern/Konami’s Scramble. The goal of the game was to seek out and destroy an alien enemy called The Gond in his subterranean fortress located deep inside an asteroid. The player piloted an advanced fighter that could fire in four directions. Gameplay proceeded through six different zones. First came a series of horizontal zones (Mountain Zone, Styx Zone, and Stripe Zone), each connected by a diagonal Rainbow Zone in which the player fought off bouncing clouds. Action then switched to a vertical Bleak Zone where enemies included floating snakes that could capture the player’s ship for points. Finally, the player entered the City of Mystery to face the Gond itself. In addition to firing, the player could fly into energy pods that granted them temporary invulnerability and allowed them to destroy enemies by flying into them. Vanguard was also Centuri’s first talking game. The most memorable feature, however, was not the voice but the music. The introductory music was Jerry Goldsmith’s theme from Star Trek: The Motion Picture. The piece everyone remembers, however, was Vultan’s Theme (from the 1980 film Flash Gordon, composed by Freddy Mercury) - the triumphant tune that played when the player snagged an energy pod. Vanguard was almost as big a hit as Phoenix, likely selling in the neighborhood of 10,000 units.

[1] Exactly when Miller and Olliges

arrived is uncertain. Allied’s 1979 annual report indicates that the deal had

become effective during the 1979 fiscal year, which ended on October 31.

However, the two attended the 1979 AMOA show in November as representatives of

Taito America. The 1980 10K report indicates that they signed their employment

contracts in April, 1980. The report doesn’t specifically say that the

contracts were for Miller and Olliges, merely reporting that Allied had entered

into 3 new employment contracts, two of them for five years. The 1981 10K

reports that one of the five-year contracts was terminated in June of 1981 –

the same time that Olliges is known to have left the company. Olliges does not

appear in the list of executive officers at the end of the 1981 report,

indicating that his was one of the 5-year contracts.

[2] RePlay,

August, 1980.

[3] While none of the company’s

literature indicates that the game was licensed, their annual report claims

that all of their 1981 games besides Challenger

were licensed.

[4] See the appendices for a discussion

of how the production numbers were estimated.

[5] Based on a 1980s list of Japanese games that identified the developer of Phoenix as "Hiraoka"

I see at present the rights to "Vanguard" appear to be owned by Taito themselves who brought the game to Japan in the arcades themselves but later released the game as part of it's "Taito Legends" series on several platforms a decade ago.

ReplyDeleteI assume, you meant Phoenix here, which appeared on Taito Legends and appears to be owned by Taito. I have always assumed Phoenix had to be a Japanese game for two reasons (in addition to Taito owning the rights):

Delete1. No US companies were doing Space Invaders clones like this in 1980, with the exception of Gorf, which came about in part because Midway owned the US rights to Space Invaders and Galaxian, making it convenient for DNA to use those elements. The game really seems too "Japansese."

2.We have no idea who designed or programmed it. Every important US game of that era from Asteroids to Berzerk to Defender, we know the people behind the game. It seems odd that no one would have tracked down the creator of Phoenix. On the other hand, there are plenty of important Japanese games of the era for which the designer is unknown in the West.

Centuri certainly licensed the game from Amstar, as multiple sources record this fact, but I believe Amstar must have first gotten the rights from Japan, either from Taito or some smaller company that Taito gobbled up in the years between the release of Phoenix and Taito Legends.

Thanks for correcting me, yes it was Phoenix I meant. If only these comments had "edit" functions.

DeleteVery well researched article. It's amazing what a couple good games can do for boosting a company's profits. By the way, there was a typo about Centuri 2001 releasing "in early 2001". I don't normally point out typos but that one was fairly critical.

ReplyDeleteI wrote a post about the possible origins of Phoenix here: http://vrofh.blogspot.com/2013/12/phoenix-puh-puh-phoenix.html

ReplyDeleteThanks, it looks like they may have licensed Phoenix from Hiraoka. Someone had actually sent me an e-mail mentioning that name earlier, but I lost it. I searched my back issues and found a few references to Hiraoka & Co. (mostly related to the licensing of Round-Up). but not much.

DeleteThere is a company called Hiraoka that makes giant tarpaulins and architectural coverings, but I don't know if it's the same company:

http://tarpo-hiraoka.com/e/

Different company. I have a link to the old Hiraoka website in the post. According to New York state records, Hiraoka New York is still "active."

DeleteBTW, I haven't found anything on Japanese sites about Star Attack.

Just to add to the confusion...over at centuri.net there's an interview with ex-Centuri employee Joel Hochberg. He claims that Phoenix was licensed from a "small Japanese developer", and they've got Tehkan (later Tecmo) listed for Phoenix. (Is it possible that due to the

Deletesuccess of Phoenix that Centuri went directly to Tehkan for the "Pleiads" license, thus "bypassing" Amstar?)

The only other game I'm aware of from Amstar is "Laser Base" which appears to have been licensed by Hoei. Round-Up, licensed by Centuri from Hiraoka, was probably developed by Amenip. Hiraoka appears to be just a Japanese licensing agent instead of developer at that time.

You might be right about Tehkan and Phoenix. As for Amenip, they are listed as the author of Fitter (Round-Up), "Naughty" (Naughty Mouse, presumably), and Macho Mouse in the US copyright records, but it looks like they were based in New York state.

DeleteYour company profile presentation very good i learn allot after the practice thanks for share it .

ReplyDelete