Anyhow, I recently came into a little more information on the early years of Nutting Associates, including what may be the first published photograph of an arcade video game, so I thought I’d do a post on the company’s history. Nutting Associates has interested me since I first found out about Computer Quiz and Computer Space. I think that both the company and Bill Nutting have gotten a bit of an unfair shake. Perhaps this article will start to correct that.

Thanks to Alexander Smith of They Create Worlds for providing the photo of Knowledge Computer and some of the other photos in this article.

Nutting Associates

|

| Bill Nutting in 1944 |

William Gilbert Nutting was born May 3, 1926[1] and grew up in the affluent suburb of River Forest, Illinois. His father Harold and grandfather Charles were executives at Marshall Field & Co, the well-known Chicago-area department store chain. After taking his first airplane ride at age 10, William developed a lifelong love of flying, and was a member of his high school aviation club[2]. After attending Oak Park and River Forest High School, William enlisted in the Army Air Corps reserves at nearby Fort Sheridan on August 24, 1944, apparently skipping his senior year of high school to do so[3]. After World War II, Nutting spent two years at Colgate University before transferring to Colorado University, where his high school classmate Claire Ulman was a student. Bill and Claire were married in Cook County, Illinois, on December 23, 1948, and in 1950, William graduated with a degree in business administration (Petersen 1992). The newlyweds then moved to San Francisco where Bill took a job at Rheem Manufacturing, a maker of heating and cooling products. Eventually, Bill decided to follow in his father's footsteps and took a job in the gloves department of Raphael Weill & Company – a massive luxury department store known as The White House for its gleaming beaux-arts façade (Goldberg and Vendel 2012).

|

| Edex's Knowledge Computer, from Cash Box, 1964 |

Nutting entered the coin-op industry in a roundabout fashion. In the mid-1960s, he invested in Edex Teaching Systems, a Mountain View company that made multimedia training equipment for the US military and other clients. Edex - the name stood for “education excellence” - had been founded by Eugene Kleiner, one of the “traitorous eight” that left Shockley Labs in 1957 to form Fairchild Semiconductor. Much later, his venture capital firm Kleiner Perkins would help establish more than 300 companies, including Amazon, Compaq, Genetech, and Sun Microsystems. One of Edex’s products was The Knowledge Computer, a “teaching machine” designed by Thomas R. Nisbet[4] that presented multiple-choice questions on strips of film. When another investor jokingly suggested putting a coin slot on the machine, Nutting took him at his word and produced a coin-op version that was sold in 1964 by Scientific Amusement Company and/or Edex (Cash Box 8/22/64; Billboard 10/24/64; 10/31/64[5]).

|

| An illustration from Knowledge Computer's patent application, filed January 7, 1964 |

In 1965, Kleiner sold Edex to defense contractor Raytheon for $5 million (Kaplan 2008). Around this time, Nutting apparently formed his own company called Nutting Corp. and began selling the game in the San Francisco area via distributor Advanced Automatic Sales (Billboard 10/23/65[6]). Save for a single reference, nothing is known of Nutting Corp. which apparently didn’t last long. At some point, Bill called his brother Dave in Milwaukee with an idea to form a company to manufacture and sell a new coin-op version of The Knowledge Computer[7]. After Bill flew to Milwaukee, the two agreed that Dave - who lived close to Chicago, then the epicenter of the coin-op industry - would build the games while Bill marketed them (Nutting 2001). Bill then visited Chicago, Detroit, and New York to talk to more distributors and learn the ins and outs of the coin-op industry.

Meanwhile, Dave set to work redesigning the game, with the help of an engineer friend named Harold S. Montgomery, with Harold designing the circuitry and Dave handling the cabinetry, projector, and other parts[8]. They eventually completed a prototype and began testing it in Milwaukee-area bowling alleys. Siblings or not, the Nutting partnership did not last long. According to Dave Nutting, the split came about because Bill's wife Claire threatened to divorce him unless he abandoned the arrangement with his brother and made the games himself. This seems unlikely however. Claire Nutting (interviewed by researcher Alexander Smith in 2017) denies ever threatening divorce and Claire and Bill were deeply religious, making it unlikely she would have done so for such a trivial reason. In a letter written to his son Craig in 2002, Bill Nutting claimed he made the decision to end the partnership because he didn’t trust Dave’s motives. There was also a rivalry between the two that stretched back to their childhood, in part because Bill had always been his parents’ favorite son. Whatever the reason for the breakup, Bill called Dave and told him to shut down his Milwaukee operation.Already heavily invested in the venture - as, reportedly, was his father - Dave decided to form his own company and produce his own version of the game called IQ Computer (Goldberg and Vendel 2012). In February 1967[9] Bill Nutting formed a company called Nutting Associates in Mountain View and Dave (at an unknown date) formed Nutting Industries in Milwaukee[10].

Without a design staff, Bill was back to square one. He sought help from a local marketing services company, who assigned an industrial designer named Richard Ball to the task. Ball placed Nutting's original prototype version on test at the College of San Mateo. Five days later, he was shocked to find the coin box filled with dimes. With newfound enthusiasm, he set to work redesigning the machine, building a new projector, converting the machine to quarter play, and making other changes, and Nutting released the game, now called Computer Quiz, around November 1967[11] (Ball n.d.; Cash Box).

Of the changes Ball made, the conversion to quarter play may have been the most significant. At the time, most coin-op games cost a dime. Pinball games often offered three games for a quarter and jukeboxes likewise offered multiple songs for a quarter, but Computer Quiz was one of the first coin-op amusement machines to feature straight quarter play for a single game. Though Sega's Periscope, which was probably released in the United States around March 1968, introduced the concept of quarter play to arcades, Computer Quiz, which was mainly found in bars, was likely the first to do so overall.

As significant as the addition of quarter play was, a subsequent change may have been even more important. Like most, if not all, coin-op machines of the time, Computer Quiz relied on electro-mechanical technology. According to Ball, the game's copper relays were a maintenance nightmare, so he approached a company called Applied Technology to design a circuit board that used plug-in relays (Ball n.d.). In the summer of 1968, Ball and Applied Technology, along with a Nutting intern, created a new version of the game that replaced the relays with solid-state, semi-conductor-based circuitry (Ball n.d.). Ed Adlum thinks it may have been the first coin-op amusement machine with an all solid-sate design (Kent 2001).

With Computer Quiz, bar patrons answered questions in one of four categories (Sports and Games, The Many Arts, etc.) After selecting a topic, the game presented four questions, one at a time on a tiny screen, along with five possible answers. Controls consisted of five buttons marked A through E. The goal was to pick the correct answer as quickly as possible. The faster a player answered, the more points they scored - in multiples of 47, for some unfathomable reason. A score of 700 allowed the player to “try for genius” with four additional questions. If they scored enough points in this round, they were rewarded with a glowing “genius” light.” Each “program” (film) contained 2,500 questions and operators could order new films when the old ones wore out - or when customers had memorized all the answers.

If the gameplay was different from other games on the market, so was the technology, even if the fact was less than apparent. At first glance, the games resembled cigarette machines as much as anything else. A closer inspection, however, showed that they were quite innovative for the time. Though the games, despite their name, made no use of a computer, they did feature an all-electronic design. There was no CRT, however. Questions were stored on a filmstrip and projected onto the screen. Rather than using LEDs, which were too expensive for a commercial product at the time, or pinball-style manual scoring reels, the cumulative score was displayed via nixie tubes. Invented at Burroughs in 1957, the nixie tube consisted of a series of glass tubes filled with neon gas containing 10 wire filaments lined up one behind the other, shaped like the numerals 0 through 9.

In addition to being innovative, Computer Quiz also proved quite successful, at least for a coin-op game in the late 1960s. Nutting Associates produced 4,200 units of Computer Quiz and Nutting Industries built 3,600 IQ Computers (Goldberg and Vendel 2012). Computer Quiz was also one of the earliest coin-op games to appeal to locations that would not consider installing a traditional coin-op game. In 1969, for instance, Nutting was invited to show the game at the annual National Putting Course and Driving Range Convention in Miami Beach (Cash Box 3/15/69). That same year, it showed the game at a menswear show and at the National Association of College Student Unions (Cash Box 6/14/69; 6/21/69).

Colleges, in fact, appear to have been one of the more popular new locations for the game. The students of Trinity University of San Antonio even used one to prepare for an appearance on the General Electric College Bowl program (Cash Box 3/29/69). Ransom White, a Stanford MBA who joined Nutting in the summer of 1967, installed a number of Computer Quiz units at various locations around campus while still a student, where it proved quite popular. Many of these locations, like The Oasis, a popular watering hole near campus, catered primarily to Stanford students and did not any have pinball or electro-mechanical games (White 2014). For thirsty college students and adult bar patrons, a trivia game was ideal. Perhaps more important, the veneer of education appealed to locations that were leery of coin-op games because of their alleged association with organized crime and gambling.

|

| Ransom White |

Overall, however, Nutting Associates was only marginally profitable. Ransom White opines that this may have been because it decided to bypass traditional distributors and sell its games directly to “operators,” some of whom were a bit shady. Richard Ball claims that another problem was the company's small, inexperienced engineering staff (Ball n.d.). In any event, Ball, White, and executive Lance Hailstone soon left to form a company of their own called Cointronics. To replace them, in 1969, Nutting hired Rod Geiman as executive vice president and Dave Ralstin as sales manager[12]. In December 1968, Nutting Associates moved from its tiny 4,500-square-foot facility to a new 18,500-square-foot warehouse and began looking to expand into new markets (Weber 1968).

|

| Above - two photos from Cash Box, 1969 |

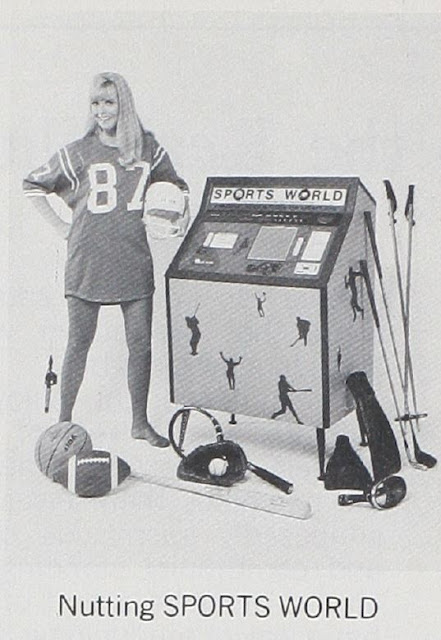

Nutting followed Computer Quiz with a handful of other games like Sports World (July 1969, a sports version of Computer Quiz), Astro Computer (September 1969, a horoscope machine). Neither came close to matching the success of Computer Quiz.

|

| Mondial's Professor Quizmaster, one of Computer Quiz's imitators |

Sidebar – Nutting (Almost) Invents the Coin-Op Video Game

According to some sources, Nutting Associates may have considered the idea of a coin-operated video game long before Nolan Bushnell showed up on its doorstep. In 1968, Richard Ball told Bill Nutting that sales projections indicated Computer Quiz would not last much longer. Told to do something about it, Ball claims that he came up with a proposal for a coin-operated video game called Space Command, to be sold to bars[13]. Before the game could be built, however, Bill Nutting reportedly fired Ball after Ball blasted him for buying an airplane with company funds (Goldberg and Vendel 2012). Ball may not have been too upset about leaving as his time with Nutting had convinced him that the entire coin-op industry was controlled by organized crime (Ball n.d.) Ball and Ransom White, along with sales rep Lance Hailstone, formed a company called Cointronics and exhibited the games Zap Ball and Ball/Walk at the 1968 IAAPA expo (Schlachter 1968). In Zap Ball, two players used compressed air to move a glowing ping pong ball through an obstacle course. Ball/Walk was a countertop game that involved maneuvering a steel ball up a pair of metal rods. In 1970, Cointronics released Lunar Lander, a solid-state electro-mechanical game, similar to Bally's 1969 Space Flight in which the player tried to land a toy model of a lunar lander on the moon. Lunar Lander used tapes of "actual sounds and voices of Apollo Flights.” White and Ball had unsuccessfully tried to obtain permission to use Neil Armstrong’s voice but decided to use it anyway since their tax dollars had paid for the space flights. Other Cointronics games included Computer Dice and Interceptor. Cointronics did not last long. By October 1970 It was out of business (Billboard 10/17/70). It never produced a video game[14]. So did Richard Ball propose the idea of a coin-operated video game in 1968? If so, he likely would have been one of the first, if not the first, to do so (at least within the coin-op industry) and it might explain why Bill Nutting was willing to take a flyer on the concept when Nolan Bushnell proposed the same thing a few years later. So far, however, no other evidence has turned up to substantiate Ball's claim.

NOTES

[1] dcourier.com/print.asp?ArticleID=57625&SectionID=1&SubSectionID=1, Social Security Death Index.

[2] The 1944 Tabula yearbook for Oak Park and River Forest High School, lists Nutting's activities as "Aviation Club 1; Roosevelt High School, Ypsilanti, Mich. 2" indicating that he might have attended high school in Michigan for his freshman and sophomore years.

[3] World War II Army Enlistment Records indicate that Nutting had "3 years of high school" and worked as a sales clerk. On the other hand, Nutting's photo appeared in his 1944 high school year book, so he may have dropped out midway through his senior year.

[4] Nisbet filed a patent on the game on January 7, 1964 with Edex as the assignee. It appears that Nisbet had formerly worked for Lockheed.

[5] Cash Box called The Knowledge Computer “an amusement machine created by Edex Corporation” and noted that it was “in use on such locations as bowling alleys, student unions, and transportation depots. It is also available as a non-coin-operated teaching device for such purposes as employee education and training.” Billboard, reporting on the “Coinmen of America” convention in Chicago, noted that “Scientific Amusement’s two Knowledge Computors, shown by Howard Starr and Bill Nutting, were given acid play tests during the three-day exhibition.” The October 31 issue included a photo of the machine. Scientific Amusement may have been a subsidiary or trade name used by Edex. The October 17, 1964 issue of Billboard includes a list of MOA Exhibitors. “Scientific Amusement Co. Edex Corp” is listed as occupying booth 64 with William G. Nutting as the representative.

[6] The brief blurb in Billboard notes that “Lou Wolcher of Advanced Automatic Sales Co., San Francisco has found a new popularity for quiz game. The Knowledge Computer of Nutting Corp., which his company distributes, has jumped quite substantially in sales during the last three months. Some 20 to 25 operators are now handling the equipment, with wide distribution in the San Francisco Bay area.” No other information on the company has been unearthed, nor is it known why (or if) Bill Nutting formed a new company. The 1967 Menlo Park city directory still lists Bill Nutting as a salesman for Edex, though the info may have been out of date.

[7] In a profile in the July 1980 issue of RePlay, Michigan distributor Gene Wagner, who later partnered with Dave Nutting to distribute IQ Computer, claims that he first met Dave at the 1963 MOA show where Dave was exhibiting Knowledge Computer. Given the game’s patent date and the fact that Billboard did not list Edex, Scientific Amusement Company, or Nutting Corp as attending the 1963 MOA show, it seems likely that Wolcher was referring to the 1964 show or a later show.

[8] E-mail from Dave Nutting to Marty Goldberg. Billboard, August 10, 1968 US Patent database. Montgomery received three patents on the device: one filed November 19, 1968, one with Dave Nutting filed June 30, 1969, and one with Nutting and Roger J. Budnik filed October 20, 1969. All three were assigned to Nutting Industries Ltd.

[9] Articles of Incorporation, Nutting Associates.

[10] In 1971, Nutting Industries was renamed Milwaukee Coin Industries (Cash Box 9/25/71). Dave Nutting later formed Dave Nutting Associates, which designed games for Bally/Midway, including Gorf, Gun Fight, and Sea Wolf, among others.

[11] The 11/67 date is from Cash Box magazine’s equipment inventory, which listed “approximate production dates” for games. Cash Box lists IQ Computer as a 10/68 release, but the December 9, 1967 issue of Billboard mentioned that Nutting Industries was distributing the game in Detroit.

[12] Cash Box (3/15/69) reports that Nutting had appointed Geiman, who formerly worked at the Micropoint Pen Company, as vice president. At the time, it appears that Hailstone had not yet left the company as the same issue mentions that Hailstone had just returned from the National Putting Course and Driving Range Convention. Ralstin’s hiring as sales manager was announced in the September 27, 1969 issue of Cash Box and his appointment as marketing director in the October 18, 1969 issue, which noted that he had been with Nutting for “several weeks.”

[13] The claim appeared in a response by Judith Guertin to an article by Benj Edwards (2011) and was repeated in the Wikipedia article on Nutting Associates - though one may have copied the other. Though neither gives a source for the information, it may have come from Richard Ball. Ball repeated the claim in an interview with researcher Alexander Smith - though it is unclear if he mentioned the game’s name during the interview. Ransom White does not recall proposing a video game to Nutting.

[14] Ransom White recalls that they produced a space game that they showed at an industry show but never released, though it appears that it was not a video game

SOURCES

To be provided after final post in series.

I'm glad to see a new article from you, very interesting as usual. I wish you all the best with the book!

ReplyDeleteIt's great to see you again! I was glad when Ed Fries made his latest post to see that you were in fact still kicking. Hoping the best for the book coming up!

ReplyDeleteI think the Nuttings both were were much entrepreneurial spirits. They both believed in technology in a way that others didn't and that's why they gave Dabney, Bushnell, and Bristow the opportunity with Computer Space. It was a perfect meeting of the minds, and while Nutting Associates didn't amount to much, DNA is one of the greatest unsung heroes in the early video game field.

Happy to see you back!

ReplyDeleteWhaaat? You're back! I was starting to worry that I wasn't going to have any more well-researched, scholarly reading on my favorite subject. Looking forward to reading this post entirely tonight, but I wanted to thank you for your work.

ReplyDeleteThanks for the valuable feedback. I think that strategy is sound and can be easily replicable. Great posts. I love this article.

ReplyDelete_______________________

Plakatdruck

Really miss your posts.

ReplyDeleteare you dead ?

ReplyDeleteNice to find some infomation on the knowledge computer,does anyone know how many were made?

ReplyDeleteThere is no information on production runs, just very scant info on vague amounts through 1963-1965. Just going by that we suspect maybe 300, definitely less than 1,000.

DeleteI bought one from a guy here in Perth Australia a couple of years ago. Don't know how it got here or when but couldn't find any info on it. I have the service/user manual and have had to adjust the mirror a few times but all still works.

ReplyDeleteWould you be able to preserve that manual? It would be very interesting to see.

DeleteI have what looks like the original and a photo copy ill have a look tonight when i get home.

ReplyDeleteExcellent! Be sure to link your findings. I'm very interested to see what you have.

DeleteI keep getting an input error when i try to link anything or reply from my computer?

ReplyDeleteI have put some photos on my google account,can you view them?

DeleteGot it! Thanks loads man. This is interesting stuff.

ReplyDeleteA couple quick takes, I would take the serial number at face value, as in the 539th unity produced. So definitely over 300, but I wouldn't suspect 1000. Part of the reason for that is the manual says Nutting Associates, which was founded in January 1966. He appears to have started making units of Computer Quiz in 1966/1967, selling them direct, then announced it officially late in 1967. However it is stamped with "Edex" which could mean that it was an older unit.

One of my curiosities was to know if there are parts providers listed on any of the internals to see where he got some of those pieces. Is anything listed in there? The manual is silent on this point, as most are.

I have the original Cointronics Lunar Lander 8-track tape. Need to archive that! Also, the Cointronics Lunar Lander used a helium-neon laser for part of its operation. I still have that laser sitting in the shop (flippers.com). I have a few other bits and pieces of the game, but nothing the player would have seen, just components used inside.

ReplyDelete